Works and “Content”: (False) Friends?

Article published on 9 January 2025

Reading time: 5min

Article published on 9 January 2025

Reading time: 5min

Used to describe just about everything and its opposite, “content” has gradually become the alpha and omega of the ever-expanding digital world. From marketing content to audiovisual content, some pieces resemble artworks while others act as bait… Through the France 2030 programme, the President of the Republic even aims to “position France as a global leader in the production of cultural and creative content.” But who—or what—are we actually talking about?

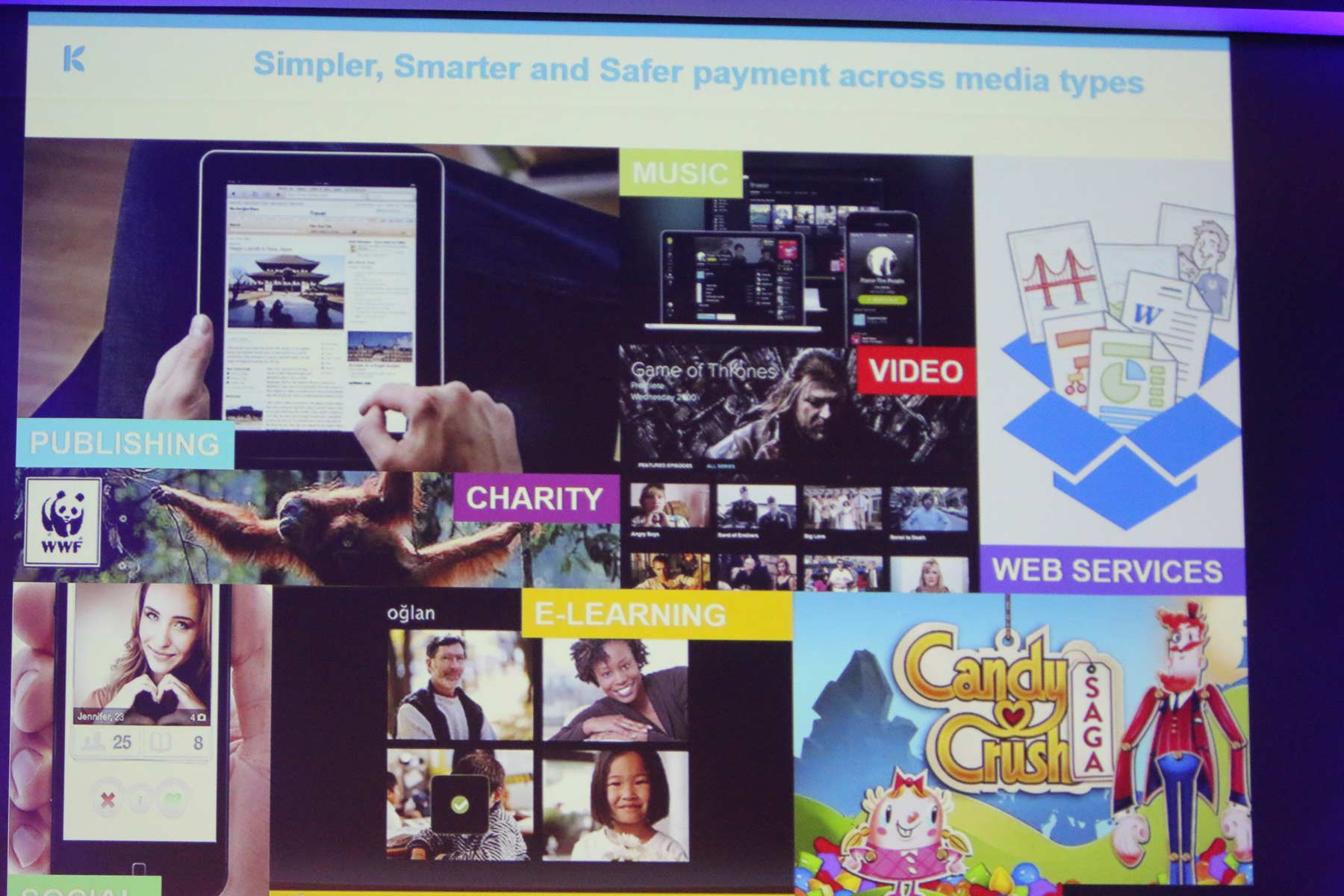

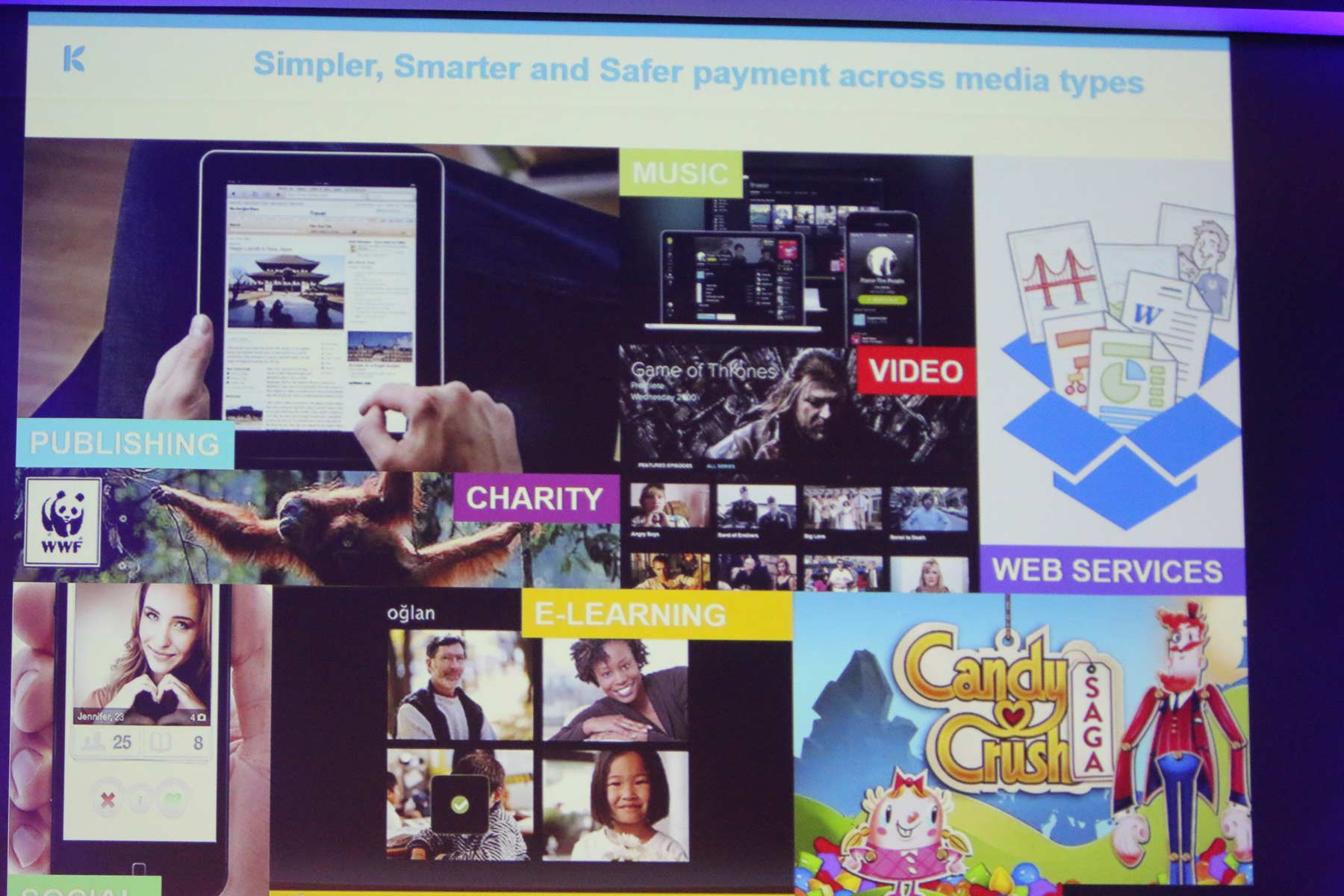

Before anything else, let us remember that a “content” is first what fills a container, what one expresses, and sometimes even what one holds back. Cultural content refers to “the symbolic meaning, artistic dimension and cultural values that emanate from or express cultural identities”¹. Digital content, on the other hand, “includes website and blog content, application software, as well as literary, musical, television or cinematographic works offered for download or streaming”². A different approach defines digital content as “one of the key drivers of online communication. It can be used to share information, ideas, solutions and promote products. It can also be used to raise awareness of a product, service or brand as a whole”³. In short, things get blurry. What exactly do these famous “contents” contain?

To which objects does the term digital content actually refer—if we narrow it down a bit? First, we think of content available on the many streaming platforms. This includes both cinematic, photographic, musical or sound-based works… and variety shows, news programmes, documentaries… Here, content refers less to a specific typology than to the multitude of elements hosted within a container.

First freeze-frame: how do we distinguish a work from content? The French Intellectual Property Code defines a work as “an intellectual creation that may take various forms: from the classic book to photography, from choreography to musical composition, including adaptations, transformations and arrangements of works”⁴. It is therefore protected by copyright. On this question, ChatGPT offers a helpful synthesis: a work is a form of artistic or intellectual creation intended to convey a personal, emotional or aesthetic vision, whereas content often responds to practical, informative or commercial needs.

The boundary between the two can be blurry, but the distinction lies in the intention, form and impact of the creation. In everyday language, a shift seems to have taken place. Works have become a subset of content. Marie Ballarini, PhD in Information and Communication Sciences and lecturer at Paris Dauphine University, adds: “The term ‘content’ comes from the American translation of content and content creator, closely tied to the development of digital tools.” She gives two examples to illustrate how fine the boundary can be between a work and content. On the one hand, the Louvre’s VR experience Face to Face with the Mona Lisa, which she considers mediation content—co-created with the museum—designed to explain and provide informational material. On the other hand, the immersive experience created for the Musée d’Orsay, Van Gogh’s Palette, offering a narrative, emotional content and interaction.

Marie Ballarini also notes that the concept of the artist varies among sectors: “In VR, the question of authorship is not so obvious because the work results from a process combining scriptwriting, graphics, interaction… Sometimes there is no narrative at all, and the work is abstract, meditative.” With the rise of digital creation, is the notion of author—and therefore of artwork—undergoing a transformation?

Second freeze-frame: consider the content that floods social networks and whose creators we sometimes struggle to identify—media outlets, institutions, influencers? These take the form of videos, podcasts, articles, images… Their aim is to inform, sometimes to sell indirectly, or to encourage visits. Here, the boundary between mediation and marketing is thin. Marie Ballarini carried out a study titled “Content Creators and Cultural Institutions” focusing notably on museum practice. She writes: “Exploring the profiles of cultural content creators, I found wide diversity in their backgrounds and motivations. Some are art historians or museum curators who chose to share their passion and knowledge with the general public; others are specialised journalists who became interested in culture and history. Others still are self-taught enthusiasts who developed digital-content production skills and built their own personal brand.” As examples, she cites art critic Margaux Brugvin and the art-loving communications professional behind La minute culture.

The blurry boundary also stems from the fact that cultural institutions themselves have developed these mediation (and promotional) contents, sometimes by internalising these skills within communication departments or outsourcing them to influencers / content creators. And though it is difficult to measure the impact of such content on in-person attendance, Marie Ballarini notes that this content “supports cultural practice rather than competing with it,” allowing—if not a massive renewal—“a diversification of audiences by removing certain obstacles and providing additional explanations.” Sociological studies, she recalls, show that new cultural practices usually emerge through accompaniment (family, partner, friends…). By activating this parasocial link—a one-way social relationship with a public personality—content creators’ messages resemble “a friend’s recommendation.”

Third freeze-frame: as the new millennium unfolds, the French President is betting on content production to “strengthen the country’s industrial model” as evidenced by the France 2030 programme and the national ambition to “place France at the forefront of cultural and creative content production”. The economic ambition is clear: “Culture is an essential lever to make France the champion of tomorrow’s economy.” One billion euros have been allocated, with goals such as “supporting the upskilling of cultural and creative industries” and “developing a new sector dedicated to immersive cultural content and metaverses.” At this point, content is no longer an end in itself but a means—a tool of competitiveness. An ambition that may appear illusory given the intense global competition… Marie Ballarini speaks of a “fantasy of creating a unicorn: we try to build an economic model by supporting start-ups and production, but distribution does not follow.” Another issue is “the discoverability of content drowned in the mass,” she adds. Underneath the surface, “cultural and creative content” carries another sizeable challenge. In his launch speech in October 2021, Emmanuel Macron openly stated: “The question is: who, today, is building the French, European and global imagination of tomorrow? And it is a competition.” Behind him, the backdrop read: “Inspire the world.”

Are contents becoming a “weapon” in a world where ideologies polarise and clash? And in this cultural battleground, are they about to replace artworks? “A country of literature, philosophy, theatre, cinema and music, France must continue to make its voice heard by showcasing its cultural heritage and developing new content and experiences,” reads the France 2030 call for proposals. Yet do a work and content truly serve the same logic? Could content denounce and critique the powers that fund it? And if not all artworks are entirely independent, how do we preserve their ability to exist without asking them to become entertainment tools, the armed wing of competitiveness—or ideology? Works may need to be protected from the temptation of becoming just another layer in powerful containers, by safeguarding their right to be free and disinterested, insolent and unproductive, even useless.

[1] Source: UNESCO – Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions

[2] Source: Office québécois de la langue française

[3] Source: Neocamino – digital marketing blog

[4] Source: SACD