The urgency of slowing down: is our relationship to time an ecological issue?

Article published on 21 October 2024

Reading time: 4min

Article published on 21 October 2024

Reading time: 4min

On 19 September, HACNUM brought together around fifty professionals at the Scopitone festival in Nantes. The goal? To debate our relationship to time in the face of ecological challenges. The conversations highlighted the need to slow down by rethinking creative processes, relationships with audiences, and production and distribution models.

The event, titled “The urgency of slowing down: changing the pace together to take action” follows a reflection initiated in 2022 at the same festival. The programme featured testimonies and presentations by artists, cultural practitioners and researchers, followed by a slow meeting—an informal, small-group discussion time designed to deepen the theme and the issues raised throughout the session.

The Slow Art movement, launched in the early 1990s, promotes ethical artistic practices that value recycling, craftsmanship, and slower forms of creation centred on process. It challenges the overproduction of artworks in a society shaped by ecological urgency and encourages deeper, more conscious observation.

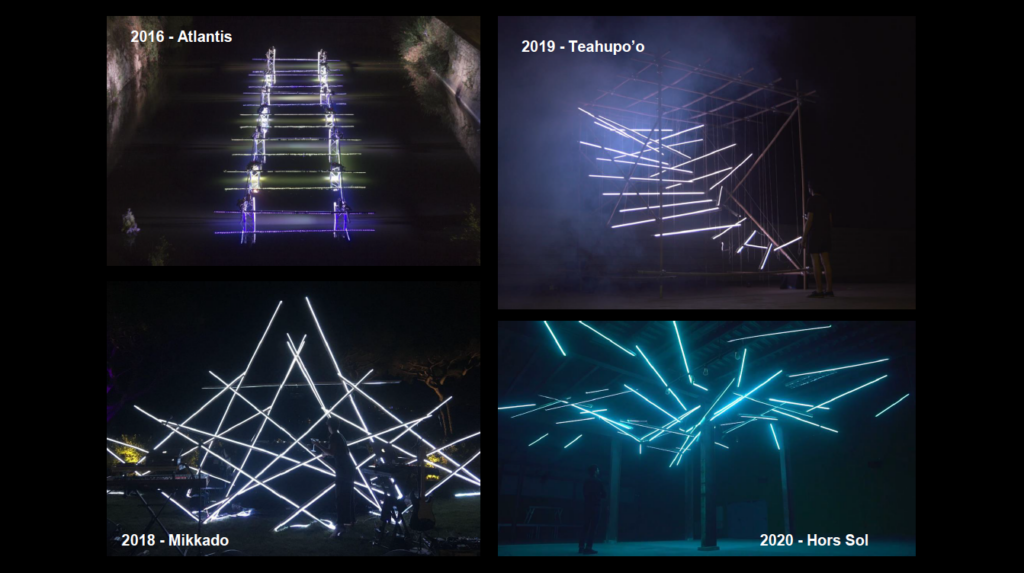

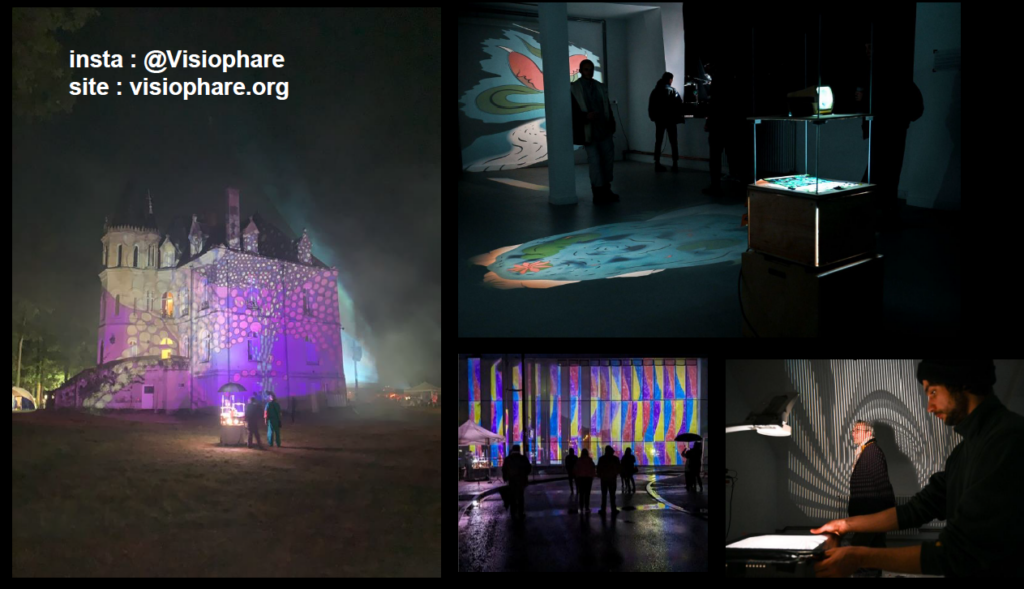

Paul Vivien, artist and designer and member of the OYÉ collective, experiments with this shift in perspective by prioritising the mutualisation, reuse and recycling of equipment and materials (including bamboo and recycled plexiglass), adopting an approach of reappropriating every stage of fabrication. Ecological impact is integrated from the outset and becomes an integral part of the artistic approach. Vivien also emphasises the importance of collaboration and knowledge sharing, which requires dedicating time within the creative process. The outcome: modular scenographic structures with low environmental impact, innovative both in process and use.

Aurélie Herbet, lecturer at Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and resident artist at Le 6b (Saint-Denis), explains that “taking the time to learn new techniques, such as tataki zome—a method of printing plants onto fabric—not only slows down production but also enriches creative practices”. She highlights that the time “lost” learning new techniques is also time gained in transmission and adds value to artistic work.

Herbet incorporates knowledge-sharing and co-creation with audiences directly into her practice, especially through fablabs and shared workshops.

“In our relationship with audiences, slowing down also means paying attention. We find it increasingly difficult to reconnect with long timeframes, partly due to digital habits” summarised one participant after the slow meeting.

How, then, can digital art help audiences become aware of time and slow down?

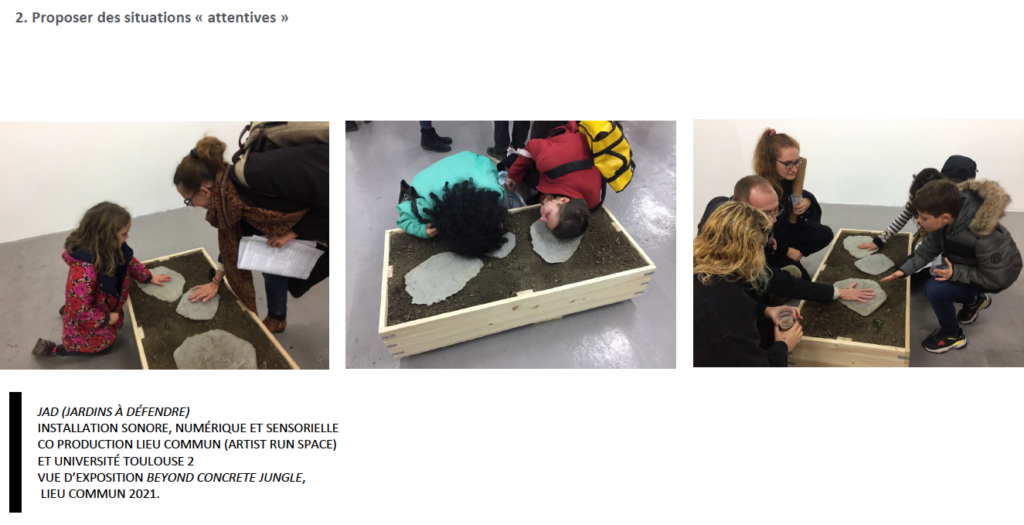

The relationship between territory, time and digital technology is central to Herbet’s work. She invites audiences to rediscover places by slowing their pace. “Digital tools can also help us take the time to better understand our environment” she explains. Through her practice, she questions urban transformation and proposes new sensory experiences. She creates “attentive” situations, such as her work Jardin à Défendre, a sound and sensory installation encouraging listeners to take their time and move beyond the immediate responsiveness imposed by digital tools.

Artist Vivien Roubaud also explores slowness. His work invites reflection on the fleeting nature of time in a world obsessed with immediacy, creating “time machines” such as giant hourglasses or sculptures designed to evolve over several decades. “We are so used to a society in constant growth that the very idea of slowing down feels counter-intuitive,” he explains. Presented at Scopitone this year, his work Salsifis douteux invites audiences to witness the accelerated blooming of a flower bud— a poetic evocation of humanity’s control over nature, and the industrial-scale acceleration of natural processes.

Faced with ecological urgency, the cultural sector is also rethinking its practices. How can we slow down when the system is structured around rapid production and distribution?

“An artist alone cannot slow down, because they depend on the structures that present their work,” explains Roubaud. Solweig Barbier, general delegate of ARVIVA (a collective for ecological transition in the performing arts), insists on the need for a collective transformation that inevitably changes our relationship to time. More sustainable production and distribution models inherently require slower rhythms; for instance, travelling by train—more ecological than flying—extends touring schedules and can have economic consequences. ARVIVA quickly recognised the limits of strictly technical approaches to ecological transition. For Barbier, “measuring carbon impact is not enough; we must also rethink economic and organisational models.” ARVIVA has therefore partnered with the European Institute for Functional and Cooperative Economics to “imagine new ways of creating value based on immaterial resources and cooperation rather than the extraction of material resources.” These transformations require strong collaboration among stakeholders, encouraging regular exchanges and knowledge sharing. “Working with everyone takes time, but it means we progress together” summarised one participant at the end of the slow meeting.

It is precisely to support such collaborations that Marie Ballarini, lecturer-researcher at Université Paris Dauphine, has launched a study with HACNUM on eco-responsible practices within the digital arts sector. Running until 2025, it aims to document concrete actions implemented across the field.

To move forward collectively, practitioners can also join HACNUM’s Digital Arts & Eco-Responsibility working group, which initiated this gathering and previously organised the 2023 event “Eco-responsibility and digital arts: a paradoxical relationship?” (see the RETEX Reconciling Digital Arts and Eco-responsibility). Active since 2022, the group’s mission is to train and raise awareness among professionals, share practices, and inspire new models in collaboration with artists.

Lucile Colombain-Corbineau

| The author of the article Lucile Colombain-Corbineau is an independent consultant supporting strategic and cross-disciplinary projects, and a trainer in collaborative intelligence and creativity. For over fifteen years, she has led projects in the cultural and creative industries, at the intersection of creation, science, and technology, including the Arts & Technology Lab at Stereolux and the Ouest Industries Créatives program. |