Permacomputing, ephemeral trend or lasting phenomenon?

Article published on 19 May 2025

Reading time: 8 min

Article published on 19 May 2025

Reading time: 8 min

Still discreet, permacomputing is beginning to draw attention in digital creative circles. Defending a low-tech, open, and degrowth-oriented approach to technology, this movement promotes more frugal tools and resource-conscious practices. Whether explicitly claimed or simply applied intuitively, it seems to appeal to a growing number of artists concerned about the impact of their work. But what exactly are we talking about when we evoke permacomputing? Is it a break from dominant practices and aesthetics? A new stance, or a continuation of alternative thinking?

If you were in Arles in the autumn of 2024, you may already have heard about permacomputing… A term clearly highlighted by the festival Octobre Numérique, which made it its guiding thread with featured artists such as Maud Martin and Mathis Clodic. “We wanted to question the place of digital technologies and this logic of escalation: always more devices, more computing power, more spectacle. What do we do when we ourselves are part of the problem? We want to make permacomputing the backbone of the next edition in 2025,” explains Vincent Moncho, director of Faire Monde, the association that organises the Arles festival. Behind the apparent simplicity of the term permacomputing — a contraction of permaculture and computing — lies a particularly rich set of creative practices worth examining. This article offers a critical perspective on the movement, situating it both within contemporary debates on digital ecology and within a longer history of environmentally responsible artistic practices. For although the word is recent, the concerns it encompasses (reducing environmental footprint, developing autonomous systems, reclaiming technologies) have animated artists from digital arts, hacking cultures, and makerspaces for several decades. But already permacomputing, like other parts of society, may appear as the formalisation of a paradigm shift already underway: less computing power, more attention to processes; less acceleration, more resilience; less spectacle, more poetry.

Born in the early 2020s within circles of artists and designers from Northern Europe, permacomputing is gradually establishing itself as a transdisciplinary field, at the crossroads of artistic creation, ecological activism, and digital technologies. This community of practice advocates for a sober, resilient form of computing that breaks with the extractivist logics and energy waste that dominate today’s technological ecosystem. “On one side there is a current of thought led by researchers, and on the other practitioners focused on the idea of changing production models, resisting obsolescence. It is a current of critique of technical thinking,” introduces Vincent Moncho.

Faced with a digital culture often driven by planned obsolescence, constant acceleration and technical escalation, permacomputing proposes another path: extending the lifespan of devices, minimising energy consumption, and reusing existing machines rather than giving in to the reflex of constant renewal. A pragmatic project, permacomputing aims to “give computers a meaningful and sustainable place in a meaningful and sustainable human civilisation within the planetary biosphere,” according to one of its initiators, the artist and researcher Ville-Matias Heikkilä. A significant publication (Permacomputing Aesthetics: Potential and Limits of Constraints in Computational Art, Design and Culture, June 2023) explores the aesthetic, cultural and political contours of this emerging movement. There are also several online resources today: first the website permacomputing.net, which hosts key publications and a manifesto; and more accessible content such as a Tracks (Arte) video produced for Octobre Numérique, now one of France’s major events on the subject. Other openly committed organisations such as Waag Futurelab (Amsterdam) or Creative Coding (Utrecht) regularly organise workshops and conferences. “I recently visited these two structures, and I feel that with permacomputing, we are preparing a form of citizen technological resistance. It resonates with current global tensions and the way Big Tech has a hold on our lives,” comments Vincent Moncho, whose words echo the techno-feudalism conceptualised by researchers such as Cédric Durand.

Beyond its critical dimension, permacomputing stands out for its capacity to reconfigure contemporary digital aesthetics. In an era of technomaximalism promoted by digital giants — enabled by graphic engines such as Unreal Engine or Unity and an entire arsenal of tools — it proposes a counter-model. Here, aesthetics are never dissociated from technique: visual and sonic forms emerge from conscious, often constrained technological choices that reject the logic of always more.

“There is now a movement that favours more limited, even obsolete forms — pixel art, the reuse of old devices — but which is not simply rooted in refusal or nostalgia,”observes Vincent Moncho. “It is a way of decoupling from dominant aesthetic norms and opening the imagination to other possibilities.”Concretely, the video game industry, with its thousands of obsolete consoles, is of particular interest to permacomputing enthusiasts, who regularly meet at game jams..

Artists such as Chloé Desmoineaux with her hackerspace in Marseille or Pierre Corbinais with his Game Boy Camera embody this indie spirit. “My goal is to take photos with an old Game Boy. Naturally, I have colour and pixel constraints. I love Oulipo, creation through constraint, and in my work this takes the form of minimal resolution and a more limited colour palette. I’m convinced that you can do a lot with very little,” explains Pierre Corbinais, without necessarily claiming permacomputing: “I had already heard about this term, but it’s not something I brandish. Generally speaking, I support degrowth; doing better with less appeals to me.” Still in the field of video games, alternative controllers — interfaces that move away from standard gamepads, mice and keyboards and question conventional gameplay mechanics — also resonate with permacomputing. The catalogue offered by Random Bazar reflects these ideas. Since 2014, Pierre Corbinais has been compiling an inventory on the website Shake That Button: “I gather all the alternative controllers I come across. Some works can be monumental and made with complex techniques and technologies, but many are also cobbled together from electronic debris or recycled devices.” Robin Baumgarten, an artist and experimental games developer based in Berlin, also fits into this category. After conducting research on AI in games and working on mobile games, he now fully dedicates himself to creating playful interactive installations at the crossroads between games and art, such as Line Wobbler, developed on Arduino. This highly minimalist game consists of only a joystick and an LED strip. By cultivating these situated, sometimes fragile, often offbeat practices, permacomputing sketches the contours of a post-digital aesthetic where economy of means becomes the central characteristic.

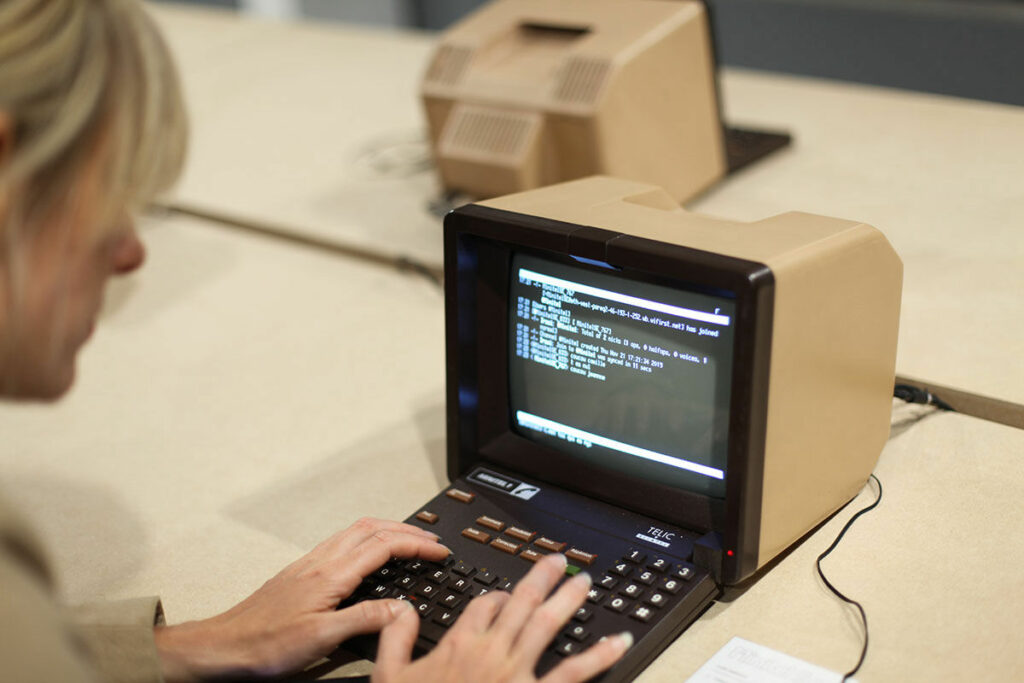

However, reducing permacomputing to its expression in video games would be reductive. While this low-tech aesthetic sometimes manifests itself through playful or retro forms, it is also rooted in approaches emerging from the maker scene and reuse cultures, such as hackerspaces like Labomedia or events like Visiophare or Makerland (see the report on the latest edition). Artists such as Benjamin Gaulon, known as Recyclism, perfectly illustrate this posture. Although he began his artistic journey by transforming NES controllers into musical instruments, his approach goes far beyond gaming. “Permacomputing is one of the appealing themes that resonate with reuse and repurposing logics. I see it as a form of applied degrowth: an aesthetic of doing with what already exists,” he explains. For Benjamin Gaulon, the strength of the movement lies in its concrete, useful dimension, in its capacity to propose other ways of inhabiting technology: more frugal, less extractive, and grounded in active minimalism. With artist Jérôme Saint-Clair, he brings old Minitels back to life (MinitelSE), exploring the possibilities of contemporary uses for these relic machines. A gesture that is both poetic and political, questioning the technological saturation of our societies and forming the starting point of a collective book, The Internet of Dead Things, to be published in 2025 (contributors include Alessandro Ludovico, Nicolas Nova, Janet Gunter, Geert Lovink…).

Rather than fully claiming permacomputing, Benjamin Gaulon prefers to invoke another concept: Zombie Media. Inspired by reflections theorised by Garnet Hertz and Jussi Parikka, “this approach focuses on technical objects that are neither fully dead nor fully alive, forgotten, obsolete or dysfunctional artefacts that inhabit our digital environments.” Against the deterministic vision of Bruce Sterling’s Dead Media Project, which asserted the inevitable disappearance of certain technologies, Zombie Media thus proposes to revive, repurpose, and prolong use — a set of ideas quite close to permacomputing.

Within this dynamic of surpassing technical limits through constraint, the demoscene — a community active since the 1980s — plays a key role. A true laboratory of digital creativity, it has explored for several decades the expressive potential of limited machines, producing visual and sonic works from ultra-reduced resources. It is therefore not surprising that Ville-Matias Heikkilä, the artist and researcher who coined the term permacomputing, is himself an active member of this scene. Figures such as Raquel Meyers or Goto80 (Anders Carlsson), emblematic artists of low-tech aesthetics based on text mode, glitch and the repurposing of old formats, are also part of this lineage. Similarly, the work of Robert Henke, whose installations and performances such as Monolake 8bit or CBM 8032 AV reactivate computers from the 1980s, reveals the expressive force of noise, glitch and consciously embraced technological constraint. Despite the obvious filiation between the demoscene and permacomputing, the communities do not always overlap: artist-researcher Florine Fouquart, a member of the demoscene since 2016, acknowledges being “sensitive to the ecological impact of a runaway computing industry that increases its energy consumption through a race for computing power and new shiny features,” yet she states “not knowing permacomputing, except for the definition of the term.”

At the same time, permacomputing also shares many points of convergence with media archaeology, a transversal discipline that examines forgotten layers of technological history: obsolete devices, abandoned formats, marginal or failed machines. In this respect, one may mention the work of PAMAL (Preservation & Art, Media Archaeology Lab), a European collective bringing together artists, media theory researchers, restorers and engineers. Including Emmanuel Guez, Amandine Chasle, Lionel Delunel and Quentin Destieux, the group offers a poetic and critical rereading of our technological heritage through acts of conservation, recontextualisation and reactivation.

Among the many concepts mentioned — Zombie Media, demoscene, media archaeology — it is undoubtedly permacomputing that most strongly captures today’s spirit of the times. More than a simple expression, permacomputing embodies a contemporary way of thinking anchored in ecological urgency, resource tensions and the need to question our relationship with technology.“This term is part of an intellectual evolution that likely resonates more strongly with notions such as ecosystem or value chain, whereas other vocabularies remained more restricted,” summarises Benjamin Gaulon. From there, it is only a short step to imagine permacomputing becoming the catalyst for a broader movement, bringing together a community of artists, researchers and activists around a critical ecology of digital technology. But at the risk of seeing the concept diluted or even appropriated?Is it better to have something accessible and watered down, or a term that is more precise and radical, at the risk of remaining marginal?”asks Vincent Moncho. The question is far from trivial. Recent history has taught us that some alternative dynamics, once institutionalised, can lose their political charge. The example of low-tech, precisely defined by ADEME through guides for companies, has sometimes been perceived as a confiscated movement. It would thus be ironic — if not bitter — to one day see a major exhibition on permacomputing sponsored by a digital multinational.

A fundamental paradox finally lies at the heart of the term permacomputing: can permaculture and computing truly be brought together? How can a worldview based on ecosystem regeneration be reconciled with technologies that are intrinsically extractive, resource-intensive, and designed for obsolescence? It is precisely this tension that permacomputing seeks to inhabit, without resolving it, but by making it the engine of a political imaginary. As its manifesto states: “Permacomputing aims to imagine such a future and achieve it. It is therefore both utopian and concrete.” A utopia, certainly. But are not alternatives born from utopias?