On the Artistic Use of Deepfakes

Article published on 18 November 2025

Reading time: 12 minutes

Article published on 18 November 2025

Reading time: 12 minutes

Propelled into the spotlight by the rise of AI, deepfakes blur our perception of reality more than ever. Many artists are now working with vocal and visual cloning tools: somewhere between technological critique and new forms of storytelling, they probe the limits of authenticity in the age of algorithms. Who are these artists? How do they challenge us in this era of post-truth? A dive into the artistic use of deepfakes.

A contraction of “deep,” as in deep learning, and “fake,” as in fake news, deepfakes (or “hypertrucages” in French) have seen explosive growth in recent months. “The idea is to digitally graft part of an image onto another, which works for both video and audio,” explains journalist Gérald Holubowicz, a specialist in the societal impacts of deepfakes. “Over time, the term became a catch-all to describe any video manipulation or identity alteration for malicious purposes,” he adds. Indeed, deepfakes have a troubling capacity to reshape real events, twist the truth, and impose an alternative narrative. This distortion manifests first and foremost in the field of pornography, often used for blackmail or revenge porn. Artists Émilie Brout and Maxime Marion tackled this terrain in Sextape (2021), an amateur porn video found online, altered so their own faces appear in it. Likewise, in 2019, Marianne Vieulès created Absolutely Yes, a reconstruction of a censored orgasm scene from Extase (1933) by Gustav Machatý.

Politics is no refuge either. In 2018, filmmaker Jordan Peele warned of the dangers of manipulation with Obama Deepfake, a viral video in which he impersonates the former president to demonstrate just how easily public speech can be fabricated. In 2019, Nixon’s image was repurposed in In Event of Moon Disaster, an installation by Francesca Panetta and Halsey Burgund at MIT.

Let’s say it clearly: deepfakes weren’t invented in 2025. Their technical foundations have existed for years in the film industry. “It’s tied to Hollywood studios who feared losing an actor mid-production,” explains artist and filmmaker Ismaël Joffroy Chandoutis, a deepfake specialist. This theme was central to Ari Folman’s The Congress (2013), which already imagined actor-cloning. “Technically, it’s a suite of tools derived from GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks). The phenomenon became widespread in 2017 on Reddit, where people could run them across multiple machines,” continues Ismael Joffroy Chandoutis. Digitally cloning performers is hardly new. As early as 2012,

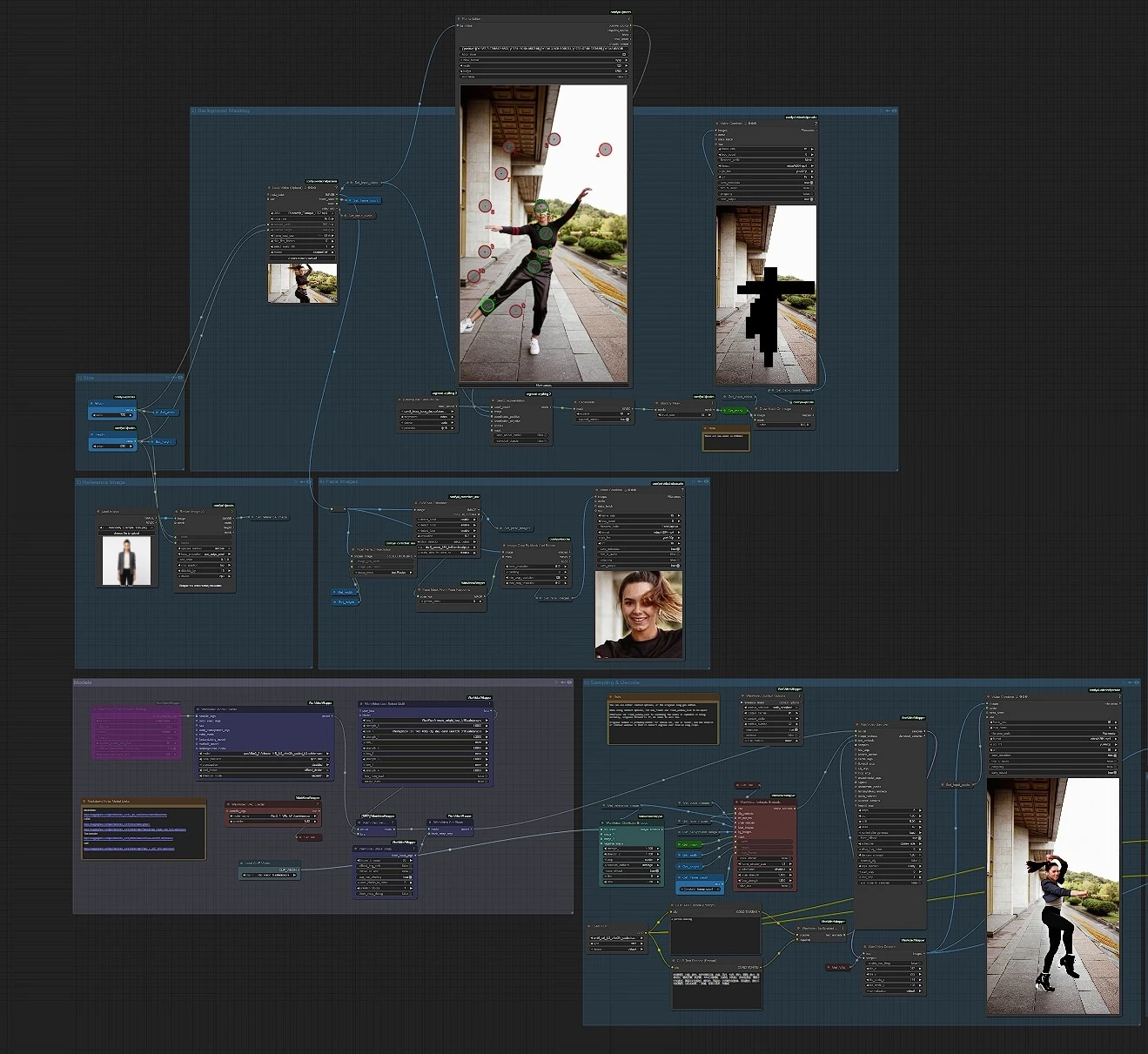

Before 2025, most visual deepfake tools relied on software such as DeepFaceLab or FaceFusion. The latter made manipulation far more accessible. “No need for hundreds of photos, sometimes one was enough. It still required skill, but the process was simpler. However, as soon as movement entered the frame, complexity skyrocketed,” says Ismael Joffroy Chandoutis, who has created interactive AI clones of Alain Damasio and David Lynch, as well as “mentor clones” like Chantal Akerman, Jean-Claude Carrière, and Aaron Sorkin, digital entities that accompany him throughout his creative process. A new wave arrived in September 2025 with the direct integration of generative AI into video tools, including Wan 2.2 Animate. “You can now use reference images to generate fully tracked visuals. From there, movements become believable: the deepfake becomes virtually undetectable,” Ismael Joffroy Chandoutis explains. Some artifacts still appear—pixel density anomalies, odd gradients. But once re-encoded, the material is smoothed out. A new discipline has even emerged: deepfake forensics, combining expert analysis and algorithmic detection.

The leap in audio technology has been just as radical. Musician DeLaurentis uses the software Musicfy. “It’s an extremely fine-tuned vocal-cloning tool. I was able to blend my voice with that of a man. It keeps my inflections and interpretation… but with another person’s timbre,” she explains in Trempo’s magazine. “I even sang Billie Jean via Musicfy. I’m nowhere near his range, but with AI I found a new vocal personality, a groove I never could’ve accessed otherwise.” Composer Benoît Carré, associated with Sony CSL’s research lab, is another pioneer of vocal cloning. His project Chansons impossibles creates imaginary duets between late artists and contemporary musicians: Dalida with PNL, Brassens singing Angèle, Joe Dassin performing Papaoutai. “You can already convert a voice, modify its timbre with RVC (Retrieval Voice Conversion). Doing it live requires massive computing power and creates latency, but we can imagine a near future where singers borrow each other’s timbre on stage,” he predicts. Meanwhile, IRCAM is actively researching detection: DeTOX for video, BRUEL for audio. Its commercial branch, IRCAM Amplify, recently released AI Music Detector, capable of analyzing audio fingerprints and spectral features with over 97.8% accuracy to determine whether a piece was generated by AI or performed by human musicians.

While deepfake technology is typically a tool of control or identity theft, for artists it becomes a space of experimentation and critique. They reclaim the tools to expose limitations and reveal societal tensions. Artistic deepfake becomes a form of metadiscourse—showing the manipulation instead of hiding it. Researcher Vivien Lloveria describes this well in Le deepfake et son métadiscours : l’art de montrer que l’on ment (Interfaces numériques, 2022). Drawing on the work of Facebook’s Monika Bickert, he distinguishes deepfakes from “cheapfakes,” which intentionally expose visual flaws, letting viewers perceive the mechanics of falsification. “A whole range of textual and visual metadiscourse teaches audiences to read these signs of manipulation,” he writes. This strategy echoes Z32 by Avi Mograbi (Le Fresnoy, 2008), in which an Israeli soldier confesses to a murder committed during his service. To preserve his anonymity, Mograbi uses a deepfake whose surface fractures, revealing the mask’s digital cracks. Ismael Joffroy Chandoutis shares this philosophy: his work on internet troll Joshua Ryne Goldberg explores the blurred boundaries between identity and simulacrum. “Asking someone to embody a figure with a thousand faces feels right conceptually. I’m not looking for Hollywood polish, I want the mask to break. This technology is only a simulacrum, and that’s exactly where it becomes interesting: when you realize it’s just an illusion.”

Artist and researcher Alizée Armet, who devoted part of her PhD to deepfake practices, advocates for the same reflexive stance. “My approach considers deepfake as an interface between the living and the computational, where the artistic gesture becomes a space of exchange born from technopoiesis. Far from simply revealing the fake, these practices allow us to imagine the emergence of non-human images and forms, opening pathways to new modes of existence and co-creation with the machine.”

Identity is explored with varying degrees of realism by many artists. In 2021, English musician and researcher

Plus largement, ces expérimentations invitent à repenser la notion de double et de l’incarnation numérique. Ces questionnements dépassent le champ des arts numériques pour s’étendre à d’autres disciplines comme le théâtre. Le collectif Obvious, en collaboration avec la Sorbonne Université, a par exemple recréé un clone numérique de Molière autour d’une hypothèse : qu’aurait écrit l’auteur s’il avait vécu au-delà de 1673 ? De son côté, la metteure en scène Christine Armanger, de la [Compagnie Louve], imagine cloner la voix de Marilyn Monroe sur sa création de dIAboli ou ressusciter la danseuse Isadora Duncan dans de faux films d’archives du début du XXe siècle (The Mirage Factory). Ou comme avec

Deepfake must ultimately be understood within a broader context: the era of post-truth, in which the mere mastery of social media can produce large-scale manipulation. It remains one of the most powerful—and ambiguous—tools for distorting reality. The collective U2P050 generates images of political figures kissing in Smack Dat, and in their film You Are Very Special, they document Trump supporters’ assault on the Capitol using AI-generated archives sourced from two years of research. Their approach borders on deepfake, though the collective prefers the term “synthetic truth,” part of a wider investigation into the redefinition of contemporary epistemology.

In a world saturated with deepfakes, attention and perception have become fragile terrains where truth and fiction merge. To paraphrase artist Hito Steyerl: images no longer just present reality—they produce it. All the artists mentioned above, working directly or indirectly with deepfake, have an essential merit: they compel us to question this radically new paradigm.

Adrien Cornelissen