Eco-diffusion: solutions to reduce the environmental footprint of artistic works

Article published on 5 January 2026

Reading time: 12 minutes

Article published on 5 January 2026

Reading time: 12 minutes

After eco-design — reducing an object’s carbon footprint right from its production — eco-diffusion is now emerging. The idea: implementing practices that make the distribution of an artwork as lightweight as possible. Here’s an overview of the initiatives already in place.

“Culture is, above all, the mobility of people, artworks, and ideas,” says Jean-Roch Dumont Saint Priest, director and curator of the Museum of Modern Art in Céret. But transporting artworks and artists comes with a significant carbon footprint. Little by little, artists and institutions are exploring alternative modes of distribution, while certain technical solutions are reaching maturity.

Gilles Jobin has been working for years on digitizing his choreographic works. In 2020, he created La Comédie Virtuelle, a live VR performance that he was able to present remotely at the Venice Film Festival in the midst of the Covid pandemic. As borders closed, Jobin and his company began experimenting with remote collaboration. They launched Virtual Crossing, an international collaborative project designed to connect clusters of artists simultaneously so they can work together from a distance. In 2021, the artist created Cosmogony, a virtual choreographic performance captured from his studio in Geneva, which can be broadcast anywhere in the world and performed live in theaters.

At the time these performances were conceived, “saving travel wasn’t even a consideration,” admits Gilles Jobin. “It was about staying alive, keeping in touch, and remaining active.” Yet, the choreographer realizes he has “transformed his activity”: almost as a “side effect,” his company no longer flies. After 60 performances in more than 25 cities, 200,000 kilometers by plane were “not traveled” by the six team members, saving over 200 tons of CO₂. This figure highlights not only the radical reduction of their carbon footprint but also the care given to their “body ecology,” Jobin notes. “When you spend your life traveling, you’re always tired, you eat poorly, it takes a toll, and it consumes time.” He doesn’t miss the live audience. “Performing doesn’t necessarily mean having an audience in front of you. They are two different mediums, neither better nor worse, with entirely new pleasures.” For him, “there’s no difference between a remote performance and one ‘in person,’” he asserts.

Remote distribution nonetheless requires rules. First, time zones need to be taken into account. “When we broadcast in the evening in Los Angeles, it’s 4 a.m. in Switzerland.” Next, a “technically robust pipeline” is essential. To create live remotely with artists connected on the other side of the world, Gilles Jobin set up a network of screens via Zoom with a computer pointed at the performance space “so we could get feedback from each other.” Managing sound was tricky: the artists wore wireless headphones, and a chat system similar to WhatsApp ran in parallel.

A DIY setup that can be found in a high-tech version at the Société des Arts Technologiques (SAT). Since its founding in 1996, telepresence has been one of the institution’s cornerstones, recalls Claire Paillon, strategic development advisor for the organization. In 1999, SAT presented Rendez-vous… sur les bancs publics, an installation connecting citizens in Montreal with those in Quebec City, allowing them to interact in real time. Since then, the organization has pursued this direction and developed Scenic, an audiovisual telepresence system that enables artists to collaborate live across multiple locations worldwide. Scenic operates on a network basis: to connect with artists via telepresence, both parties must have a station. Today, 28 stations are deployed, including 25 in Quebec, two elsewhere in Canada, and one in Avignon, France. Equipped spaces primarily host performing arts projects, but also cultural mediation, conferences, and training sessions. SAT can also rent the station along with staff hours for setup; to improve transportability, technical teams developed a compact station that fits in an airplane cargo hold. Teams are also developing a Raspberry Pi–based system, portable and self-contained, designed to be as small, energy-efficient, and accessible as possible for individual artists.

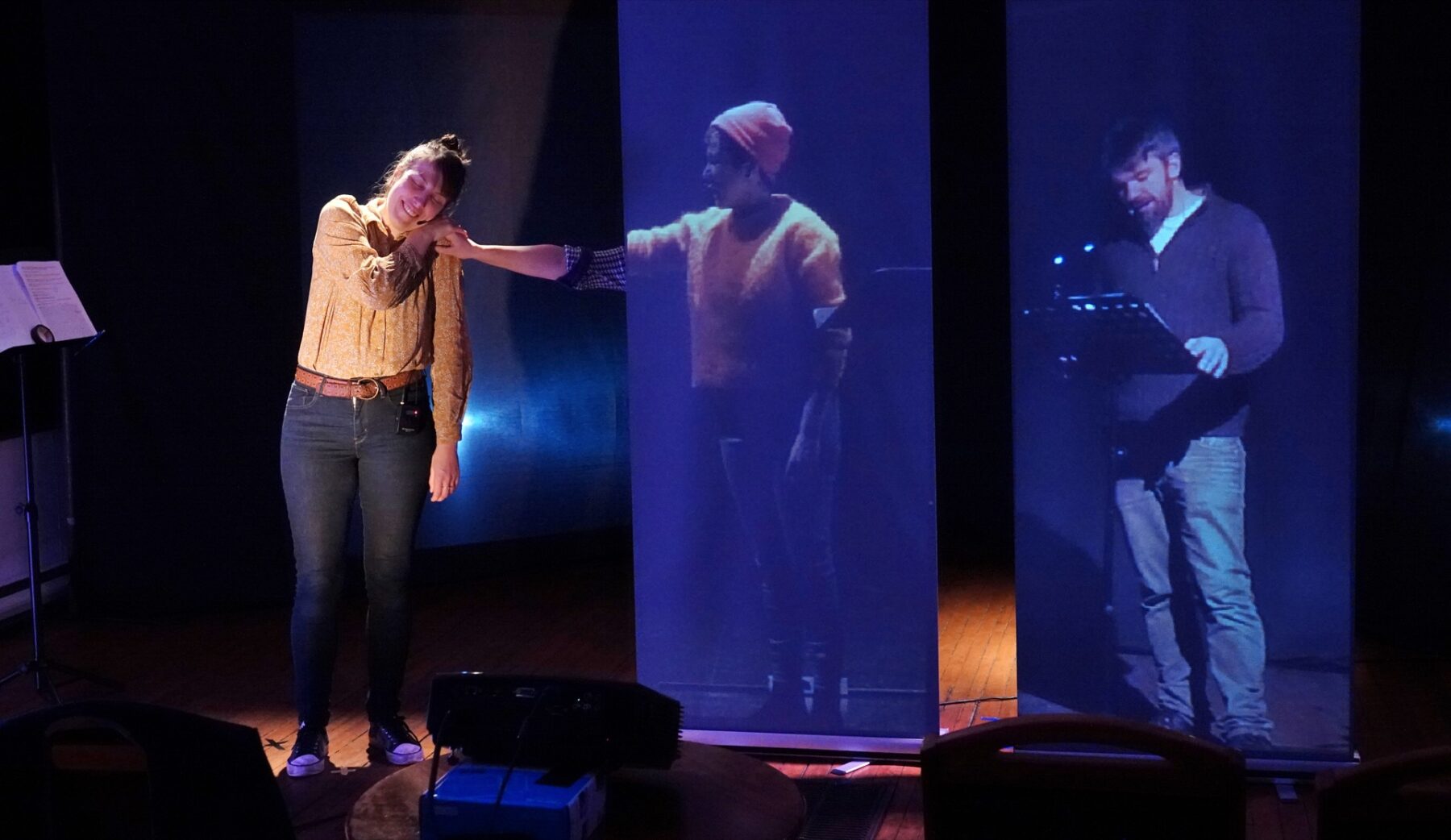

Among the projects realized with Scenic is Bluff, a work that brings together three performers in three different cities, each connected to a separate audience. “Often, they perform as if they were together,” describes Claire Paillon. “Sometimes, they step out of human scale, project themselves into a dollhouse, use close-ups. In these moments, the artists take ownership of the technology and push the boundaries of the codes.” Another project in the works involves improvisational theater tournaments, allowing leagues to compete without traveling. Like Gilles Jobin, SAT developed its tools primarily to expand artistic opportunities for creators; the ecological benefit came only later. But just as the choreographer highlights the ecology of the body, Claire Paillon emphasizes social ecology: in a country where cities are separated by hundreds or even thousands of kilometers, telepresence enables projects to reach the entire territory, not just major urban centers, she argues. For example, Rouyn-Noranda, a town of just over 42,000 people more than 600 km from Montreal, has “one of the most dynamic arts organizations” in the telepresence network, Claire Paillon proudly notes.

On the installation side, there is also a push to redefine transportation methods. Since 2021, with Adopte un glacier, artist Barthélemy Antoine-Lœff has been hosting an ice cream freezer under perfusion in people’s living rooms. The artist moves it from one location to another by bicycle, and he didn’t hesitate to travel to the Venice Biennale in 2024 using the same mode of transport. For Guillaume Cousin, the strategy is somewhat different. This visual artist creates monumental works often weighing several tons and occupying around ten cubic meters. He is currently developing a model to relocate the production of his works to the place where they are exhibited. His art makes this possible, he explains: “Unlike contemporary art, in digital art, the work itself has no speculative value. Its market value is tied to the service provided.” In theory, he could reproduce his works anywhere in the world to avoid transport. To achieve this, he focuses on using accessible and easy-to-source materials, such as plywood, and relies on technological advances in 3D printing and CNC machining robots. The idea is then to store the piece locally and rotate it. At the moment, Cousin is still in the research phase. The biggest challenge is obtaining accurate sourcing information for his materials: if the plywood sheets have already traveled around the world four times, the ecological benefit of this diffusion method is reduced. For his next work, L’éternel Retour, which he will unveil for the first time at the ]interstice[ festival in Caen, part of the piece was fabricated on-site. For the rest, he shipped flat-packed boards in “Ikea style,” a method that allows him to use parcel delivery rather than maritime or road freight.

For all artists moving in this direction of eco-diffusion (Gilles Jobin prefers the term “decarbonized distribution”), ecological sobriety goes hand in hand with economic frugality. “The show costs 3,500 euros for a performance, all-inclusive,” Jobin explains. “I wanted to create a performance that was easy to host and inexpensive for organizations: no hotels, no travel and per diems, no one to pick up at the airport.” Guillaume Cousin takes a similar approach. “It doesn’t make sense to spend 10,000 euros on transport when the artists’ fees are only 5,000 euros.” According to his calculations, exhibiting his piece Le Silence des particules in Canada would have cost 15,000 euros for transport, while reconstructing it on-site would cost 8,000. “For a single exhibition, it’s barely worth it, but if you rotate the work across two or three venues in the region, it pays off!”

Pooling resources is also what Jean-Roch Dumont Saint Priest, director and curator of the Museum of Modern Art in Céret, practices. To reduce both the carbon footprint and the cost of transportation, he coordinates with other museums to collect artworks. Such coordination requires strong networks. Dumont Saint Priest cites, among others, Musées Occitanie, a network bringing together over 250 professionals in the field. The Museum of Céret also collaborates with La Malmaison, a contemporary art center in Cannes, on museum catalog publications. The economies of scale allow them to access higher-quality materials, he explains, with ecological criteria and local sourcing in mind.

In the world of art institutions and establishments, eco-diffusion is a major topic, the director-curator insists. This approach, focused more on collaboration and proximity, requires “reinventing the narratives,” he explains. “Audiences often expect museums to showcase big names, prestigious works from far away. We want to argue that great emotions are not determined by the carbon cost of the artworks.” Last year, the museums of Céret and Collioure co-organized the artists’ bike race, a day-long tour involving around forty artists traveling between the two towns. “The impact on attendance is minimal, but it shows the commitment and effort we want to make.” Above all, the director notes, reflection on eco-diffusion is still in progress. “We have every reason to share our ideas!” he declares. The call has been made.

Elsa Ferreira