Création (artistique en environnement) numérique : de quoi parle t-on ?

Article published on 18 February 2026

Reading time: 8 minutes

Article published on 18 February 2026

Reading time: 8 minutes

At first glance, the term “digital creation” can seem both outdated and overused. Outdated, because digital tools are now commonplace in performances and exhibitions. So how can we meaningfully situate digital creation today? Overused, because of its widespread adoption within the creative and cultural industries. Does it still truly refer to art? A brief semantic debate, set against a historical backdrop.

Today, the term digital creation is frequently used—by institutions such as the Ministry of Culture, the CNC, and the Institut français, as well as by cultural organizations and artists themselves. Yet it can be difficult to grasp exactly what the term encompasses. This was, in fact, the primary finding of a study conducted by DRAC Bretagne in late 2023: “The subject is complex, as it involves notions of hybridization across media, practices, and spaces… A wide range of aesthetics exists, as technological evolution has profoundly transformed practices and enabled new forms to emerge.” A fuzzy term, with boundaries that are both broad and narrow, it fuels ongoing debate among professionals, artists, and institutions—and echoes the (longstanding) controversy surrounding the very nature of digital arts.

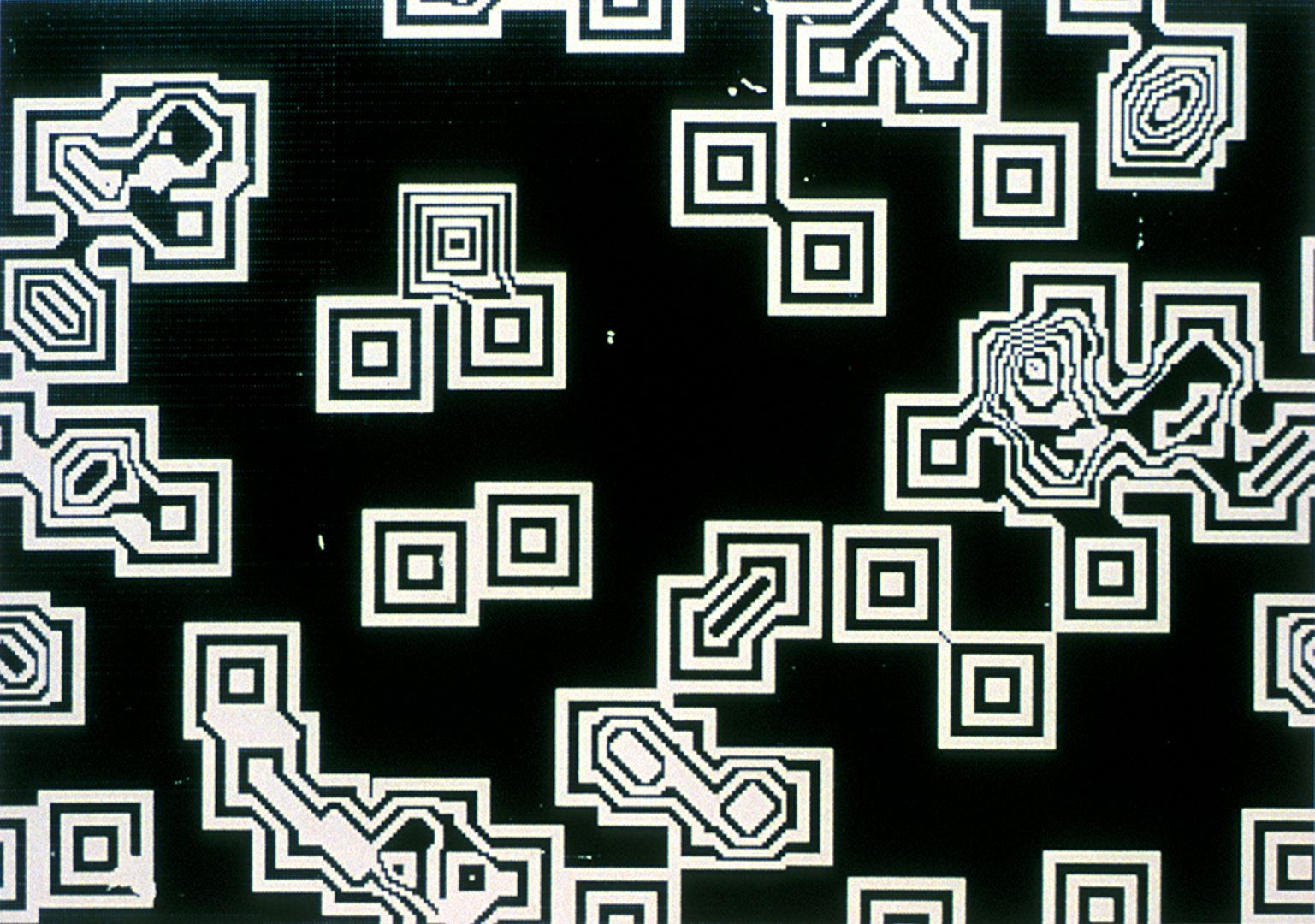

It is through a historical lens that Franck Bauchard, Coordinator for Digital Policy at the Directorate-General for Artistic Creation (DGCA) within France’s Ministry of Culture, approaches the issue: “Since the early days of digital creation, there have been debates over the terminology.” Without delving into a full art history lesson, this perspective helps explain why controversy has long animated this artistic field. In the 1950s and 60s, the pioneers of computer art were often engineers or scientists—such as Lillian Schwartz and Kenneth Knowlton—with the computer at the very core of the creative process, sometimes leading to questions about whether the resulting works could even be considered artworks. With the advent of the personal computer, digital art gradually became more accessible, and artists began using the medium to create works in many forms (video, music, images, etc.), later supported by the DICRéAM (Multimedia Creation Support Program) in 2001 (editor’s note: discontinued in 2022). At the time, the debate centered on whether one needed to know how to code to be considered a digital artist. More recently, the question has flipped: in a world where digital technology is everywhere, has the internet become less a tool for creation and more a subject or an aesthetic in itself? As technologies evolve rapidly, digital creation remains in constant flux—both in its techniques and in its intentions. Franck Bauchard refers to what he calls the “original sin” of digital arts: initially defining themselves through technology. “The challenge now is to move beyond this association with the medium and to engage artistic issues through technology,” he explains.

Justine Emard is regularly programmed by venues and festivals within this ecosystem. Yet nowhere in her biography do the terms digital creation, digital art, or digital arts appear. She simply presents herself as an artist. “Throughout my career, I’ve always moved between the contemporary art world and digital arts, but labels have always bothered me,” she says. “We’re long past the time when an artist worked with a single medium.” Her practice combines photography, video, and virtual reality, among others. She seeks to “question the media of our time,” intersecting artistic creation with technological exploration and neuroscience. For Justine Emard, “the term digital creation is reductive, because there is a real physicality in my work—a material embodiment of software or code through installations, sculptures, and so on.” These debates regularly surface within digital culture and hybrid art circles. In 2024, a new term became institutionalized alongside the creation of five regional hubs for artistic creation in digital environments. Emerging from discussions between sector professionals, the DRACs (Regional Cultural Affairs Directorates), and the DGCA, the word environment was deliberately paired with digital. “Technologies are environments we inhabit. The notion of environment suggests that they affect us and transform us, within a relational framework,” explains Franck Bauchard. This nuance also resonates with Justine Emard, for the openness it implies—though she personally prefers the term ecosystem, which she finds “more dynamic” and better suited to expressing the interactive processes at work.

As a dedicated policy framework takes shape, one key question remains: what criteria determine whether a work belongs to the field of digital creation? Where does the boundary lie between artistic creation in a digital environment and, say, a theater production that uses video? “Artistic creation in a digital environment is a distinct field, but one that is also open to artists who wish to engage with complex digital processes,” answers Franck Bauchard. For him, the distinction lies in the creative process itself—much like Chimères, a research and experimentation program conducted between 2018 and 2023 with DGCA support, open to all creative disciplines and aimed at supporting hybrid artistic writing and contemporary uses of technology. The reflective dimension of these works stems from the idea that “to question technologies, you have to explore them,” Franck Bauchard argues.

For Anne-Laure Belloc, Director of Digital Arts and Culture Programming at Stereolux and representative of the Pays de la Loire hub for artistic creation in digital environments, complexity of process is not a necessary criterion: “A work can simply revolve around a reflection on technology.” This is the case, for example, with Alice Bucknell, programmed at the Scopitone Festival in 2025 with Align Properties, a video work exploring the relationship between spirituality and big data.

What if the key word isn’t environment so much as artistic? What if the real debate is about the purpose of digital creation? Justine Emard points to a persistent “confusion” with the creative and cultural industries, where the term is frequently used. Anne-Laure Belloc, for her part, sees certain contents as “applied forms of art products.” Academic programs in Digital Creation further illustrate the term’s polysemy. “The label ‘Digital Creation’ brings together a wide range of pedagogical practices and professional scopes. Its use by the Ministry distinguishes it from other master’s programs in fine arts, audiovisual production, or video games,” explains Samuel Gantier, Associate Professor in Information and Communication Sciences at Université Polytechnique Hauts-de-France, where he heads the Graphic and Interaction Design track within the Digital Creation Master’s program.

Bien qu’aujourd’hui, le terme « création artistique en environnement numérique » semble faire consensus, Franck Bauchard ne manque pas de rappeler qu’il reste en perpétuelle évolution : « Toute définition est forcément instable et demande à être régulièrement interrogée par les parties prenantes, en concertation ». Suite au prochain épisode…

Julie Haméon