Creating with AI: ecological alternatives do exist

Article published on 29 September 2025

Reading time: 15 minutes

Article published on 29 September 2025

Reading time: 15 minutes

Tiny models, solar-powered models, residencies exploring AI and ecology… While most artists today rely on conventional Big Tech models, another segment of contemporary creation is exploring more frugal and critical approaches. Less energy-intensive—sometimes at the cost of a slower creative pace—these practices shift our imagination and challenge dominant representations. This article analyses these alternatives, showcasing emerging models and highlighting significant artistic contributions.

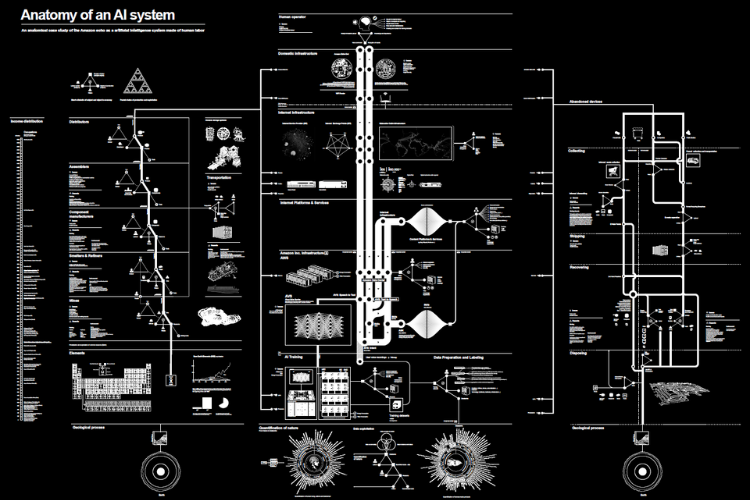

In the background lies generative AI and its large language models (ChatGPT, Claude, Mistral…). Their environmental cost—now better documented despite the lack of transparency from tech companies—is immense: staggering energy consumption tied to training, colossal infrastructures, and the continual production of increasingly powerful hardware. This capitalist and extractivist system is powerfully illustrated by artist-researcher Kate Crawford and artist Vladan Joler in their now famous Anatomy of an AI System. In this context, AI-assisted creation can quickly feel guilt-inducing, even at odds with the ecological and social values upheld by many contemporary artists. Let us be clear: “frugal AI” is likely more of an oxymoron than a concrete reality. Yet AI creation is not condemned to rely solely on the models powered by tech giants. There are as many ways of working as there are artists, and some deliberately choose more restrained, more ecological paths. In a world of “for or against”—AI included—where viewpoints tend to polarize, there remains space for alternative practices. Hence the need to make these dissenting initiatives visible.

Very schematically, the functioning of AI rests on three pillars: a model (with a greater or lesser number of parameters), a dataset, and the computing power required for training. The best-known LLMs and image or video generators (Sora, Midjourney…) rely on billions of parameters, draw on massive quantities of web-sourced data, and require colossal computational power, made possible by GPUs—graphics cards over which NVIDIA now holds a near-global monopoly. By nature, these models are therefore highly energy-intensive and difficult to reconcile with ecological concerns: climate, biodiversity, water cycles… And the issue begins, first of all, on the technical level. “It’s the number of parameters that remains decisive, because the relation is fairly linear: fewer parameters mean faster inference. The architecture of the model directly influences execution speed, memory usage, and energy consumption,” explains Charles Bicari, multimedia integrator at the SAT in Montreal, who has spent several months working on AI programs applied to artistic creation.

Another defining feature: their generalist vocation. These generative AI models can accomplish a multitude of tasks without being limited to a specific use. But in the field of artistic creation, needs differ substantially. “Is ‘the bigger, the better’ really a reliable model for creation?” asks Baptiste Caramiaux, researcher at the Institute for Intelligent Systems and Robotics (ISIR) at Sorbonne University in Paris. “It is entirely possible to avoid multitask models and instead use small models. Their advantage is precisely that they are oriented toward a specific task. Artists can calibrate and personalize them, and they become a kind of instrument.” Historically, many artists did not wait for the 2022 AI boom to explore machine-learning models. For decades, some have experimented with them—for instance at IRCAM, through research on gesture recognition and sound interaction. “This is the case for Marco Donnarumma or Laetitia Sonami,” notes Baptiste Caramiaux. “For others, like Atau Tanaka, it is even a way of performing, since the model is trained live.” These small, decentralized models also offer artists direct control over their datasets, which are relatively lightweight compared to LLM-based workflows (see our article “The Effects of the Dataset”). Their energy consumption remains modest, and they can be trained on local servers rather than in the cloud. A paradigm that runs counter to the technomaximalism of AI giants.

In this context, several actors in the digital arts ecosystem are experimenting with new models, with the ambition of making them available to the artistic community in the medium term. This is the case of the MUTEK AI Ecologies Lab, which launched in 2025 a residency call on the theme of AI and ecology. “We had many conversations with artists eager to work with AI without compromising their values or ethical commitments. The idea was less to create artworks than to develop tools that cultural and creative industries could appropriate, and release them as open source,” explains Sarah MacKenzie, director of MUTEK Forum. Six projects were supported with technical assistance from the SAT for implementing small models running on microprocessors (such as Raspberry Pis). Among these projects were You, Me, the Lichen & Spore, an immersive installation using AI to interpret biological data from organisms sensitive to environmental variations, and Environment Art in The Garden, which explores the generation of immersive 3D landscapes for use in animated cinema. Presented as proof-of-concepts during the latest edition of the festival, these works form a first step. “It was a starting point; we need to continue every year, with the aim of also measuring the concrete ecological impact of these projects,” adds Sarah MacKenzie (a carbon calculator for this type of model has been prototyped by Harvard University).

For Charles Bicari, who oversaw the technical development of the projects, the task remains demanding: “These are complex implementations, and no out-of-the-box solution exists yet. Despite this, we are committed to making a dozen small models accessible through Ossia Score (install the software and download the appropriate models).” More broadly, the SAT now stands out in the ecosystem through its clear intention to make this research visible and understandable, notably through pedagogical publications dedicated to Tiny Models (also known as Machine Learning on Microcontrollers or TinyML), already documented in scientific literature in recent months.

Another notable initiative for its ambition is The Feral, a project set to be launched in France in 2026 following the recent acquisition of 15 hectares of forest in the Limousin region. Here, the aim is not only to master tools, but to rethink the very conditions of our humanity in light of technological transformation. The Feral is grounded in a living ecosystem and fully embraces a contemporary paradox: “The more our technologies develop, the more the Earth deteriorates. We want to think about this paradox from within, without trying to solve it but instead making it the material of a practice,” says its director, Ida Soulard. Artist Grégory Chatonsky is associated with the project, with the goal of designing closed-circuit models powered by solar energy. Unlike the infrastructures of technological giants—designed to handle millions of simultaneous requests—the AI at The Feral will be conceived for a single site, offline, thus lowering consumption. It will not seek the supposed omniscience of a generalist AI but will adopt a limited form of learning, adapted specifically to its environment, exploring alternative approaches such as JEPA or video-based learning. Finally, it will be powered by solar energy. The AI will therefore follow cycles of wakefulness and sleep, like a living organism, challenging our dependence on constant availability. “This approach leads us to a question: how do our uses evolve when technology adopts circadian rhythms? When it sleeps at night and wakes with the sun?” continues Chatonsky. “It is a radical rethinking of our relationship to digital tools, synchronizing the artificial with the natural, replacing permanent availability with intermittence.”

These alternative models, however, remain difficult to develop. The Choral Data Trust Experiment by artists Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst is a case in point. Since 2024, Serpentine and Future Art Ecosystems—an organization aiming to build infrastructure for the development of art and technologies—have supported the project. Its objective: to test new approaches to governance of AI training data, a peripheral topic but one intimately connected to ecological concerns. A publication detailing the results of the experiment emphasizes the central role played by cultural institutions in developing alternative models, the need for significant resources, and the necessity of technical expertise. In other words, without political strategy and structural support, it is difficult to imagine alternative models being widely adopted by artists (see our article “The Real Cost of Generative AI”).

Another obstacle lies in the technical implementation of these open-source models. In a previous article (“AI, Proprietary Software or Open Source”), we explained that, unlike proprietary software—with its ergonomic interfaces and marketing power—open-source models, despite available resources (tutorials, libraries, active communities), often remain more austere, more technical to configure, and more confidential. Even more so when the models concerned are those recognized for their environmental attributes. “If you’re not passionate about the topic, it is very difficult to access the right resources,” notes artist Léa Collet, who explores the interconnections between botany, living systems, and technology. “I do a lot of workshops in schools, and it’s often difficult to deploy an open-source AI on students’ devices.” Her project Racines, presented at Le BAL, was—out of pragmatism this time—created using proprietary software.

Léa Collet’s approach deserves close attention. “I spend a year making a project, finding a collective dynamic,” she says. Her work Digitalis emerged from workshops conducted at a middle school in Tourcoing. Over several months, students explored, through introductory workshops, the relationship between nature and technology. This was followed by scenario-writing sessions around a simple, poetic idea: imagining the students transforming into plants. The students then sent their questions to scientists, enriching the project with documentary and research-based content. The final stage involved working with open-source models deployed locally. The students’ faces were filmed and then transformed into flowers. The process thus deconstructs two myths perpetuated by tech giants: the myth of individualized creative practice—challenged here by the participation of an entire group—and the myth of productivity, usually measured in terms of execution speed. In his latest work Deepscape: Longitudinal, artist-researcher Hugo Scurto worked with a generative AI model based on data gathered through his year-long observation of Cape Morgiou in the Calanques National Park in Marseille. He too embraces a creation process aligned with the rhythm of his subject. “The collection of sound, visual and personal data lasted an entire year,” he explains. “I had to work around environmental constraints—whether the park was closed due to wind, or overcrowded with tourists.” In total, the dataset took a year to gather, followed by another year to conceptualize and develop a form that felt coherent.

These examples of reappropriating the creative process are summarized by artist Justine Emard: “As artists, we don’t have control over everything, but we do have control over the ecosystem of the work.” She illustrates this with her video-game-installation Chim[AI]ra (2024). In this project, one of the central data points is the activity of the computer’s graphics card: the ecosystem represented in the game evolves according to the layers of rendered imagery. “I wanted to establish correspondences between what physically happens in the world and what unfolds within the game. It is a way of returning to a kind of anatomy of the image—understanding how a video game is composed.” Thus, the virtual universe of the work, initially overflowing with visual effects, gradually becomes more sparse. As the GPU’s consumption decreases—visualized through an integrated graph—the image is reduced to its essential structure, down to wireframes.

If one side of the challenge involves redefining the modes of AI-augmented creation, the other lies in asserting an artistic discourse capable of questioning our representations of this technology. Many artists work not only with AI, but also on AI, turning it into an object of critique. Consider several recent creations. With Carbon Technostructure, currently supported by OHME, Guillaume Slizewicz seeks to make visible what is usually hidden: the environmental cost of computational processes, and more specifically the energy consumption of GPUs. In Echologic, presented at Octobre Numérique, Sébastien Thon addresses the question of deep time. The work imagines an AI returning to the earth, dialoguing with a neighbouring permaculture garden to explore ecological responsibility. Finally, Cry to the Water, by artist Chipo Mapondera, opens the ecological field to postcolonial issues. This immersive experience invokes an AI nourished by ecological knowledge rooted in ancestral Tunisian and Zimbabwean traditions, to address water scarcity, climate crisis, and resource-justice concerns.

Faced with the univocal model imposed by Big Tech, all these structures and artists demonstrate one thing: an alternative AI, more aligned with the environmental challenges of our world, is not only possible—it is necessary.