Collaborating to Better Preserve? The Challenge of Conserving Sound Works

Article published on 15 September 2025

Article published on 15 September 2025

The conservation of digital works raises complex questions: how can we deal with software obsolescence? How can we ensure the long-term survival of creations when computing environments are rarely interoperable? Or when protocols differ from one organisation to another? Explored at length in a previous article, these issues are particularly topical for sound creation, as a collaborative platform for conservation is due to be launched at the end of the year.

For several decades now, sound creation—whether musical composition, sound design or multimedia installations—has relied on the rise of digital and immersive technologies. Yet although awareness of the fragility of this heritage is growing, conservation practices themselves remain far too marginal. This shortfall cannot be explained solely by a lack of human or financial resources. It is also due to the absence of shared protocols and common databases, which are nonetheless essential to ensuring the durability of works. As artist-researcher Julien Ottavi, artistic director of APO33, a cultural project in Nantes at the crossroads of sound art and digital arts, points out: “Archiving and documenting is work that takes time, and it is not the primary mission of artists, organisers or technicians.” By way of comparison, IRCAM is one of the rare institutions that has the necessary human resources: there, archiving and documentation are an unavoidable stage of every creation. This work demands considerable energy, but it is systematically integrated into the process. “The ten or so computer music designers at IRCAM are responsible for archiving and documenting. We always dedicate time to this after the creation,” explains Serge Lemouton, one of the institution’s “RIMs” (réalisateurs en informatique musicale).

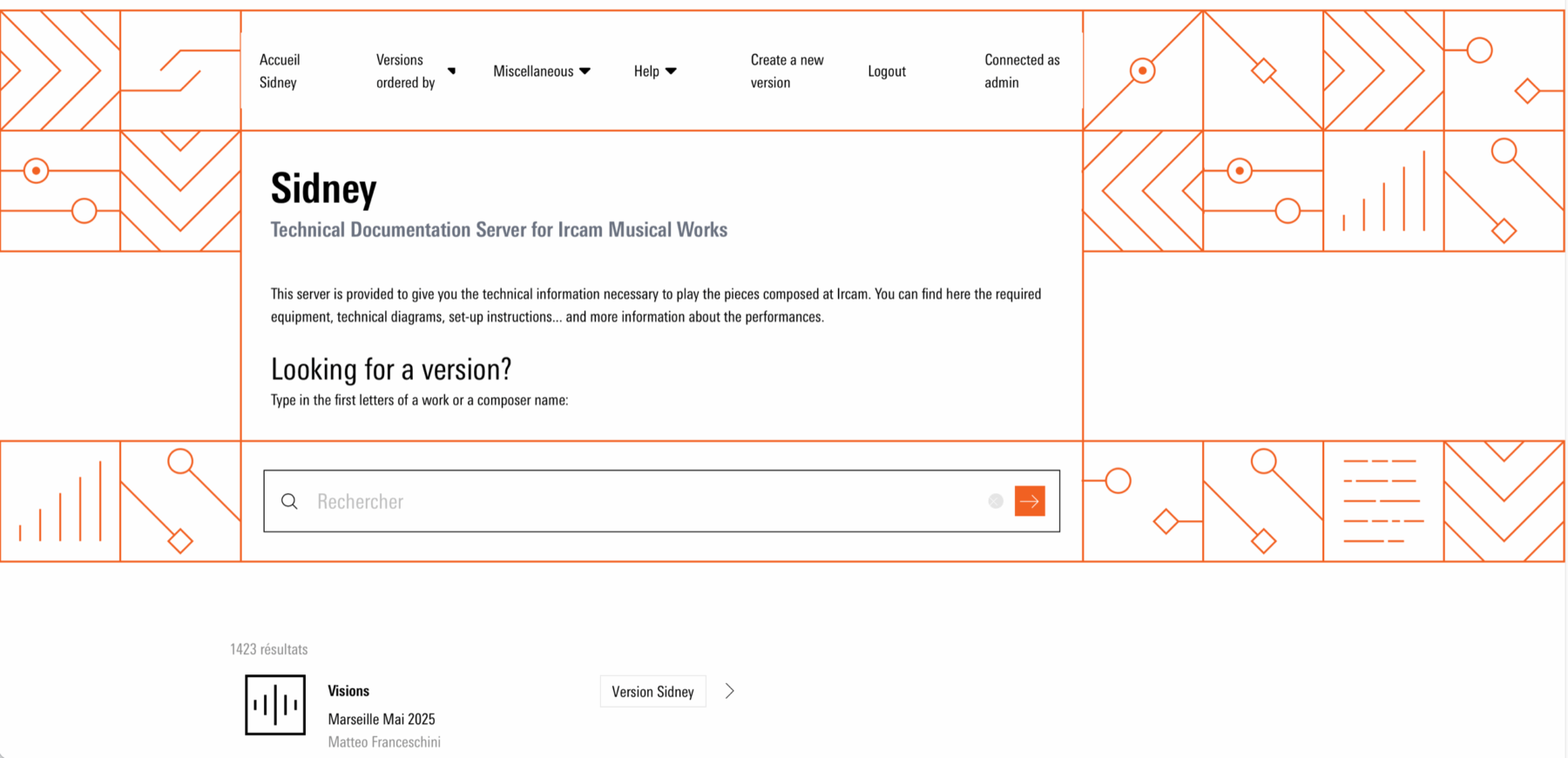

One must still decide what to conserve, and for what purpose. Should priority be given to preserving the final work? The creative process that made it possible? Or both at once? Far from being theoretical, these questions determine the very future of dissemination. “Are we conserving for online dissemination, for physical formats, for a dedicated platform?” asks Julien Ottavi. At IRCAM, the aim is to make it possible to “reactivate” a work—to perform it again in the future. As Lemouton reminds us: “That means describing precisely the technical setup used: the software, the patches, the videos, the lighting, the synthesisers, and so on. This documentation is the key, the real instruction manual.” To centralise this work, the institution maintains an internal database called Sidney, designed to archive and document each creation. But this exemplary approach immediately reveals its limits at the scale of the sound-creation sector: there is no single model of documentation, no universal standards. And the issue becomes even more complex in the era of hybridisation, where sound practices unfold across an almost infinite variety of forms and formats.

Historically, questions of dissemination and preservation have been approached from the perspective of music publishers, who are concerned with ensuring the collection of publishing and performance rights. In the same spirit, the sound art gallery ((le son 7)), located in Capestang in the south of France, has adopted a conservation policy that focuses more on the work itself than on the technical conditions of its production. Responsibility is therefore transferred to collectors, who are invited to convert the files in the event of changes to formats. “We use the .wav format, but we anticipate the arrival of another format in the years to come. Conversion to different formats is allowed,” explains gallery co-founder Andy Footner. This flexibility is explicitly written into the rights-transfer contracts: the buyer has the “right to reproduce the work, in order to make copies by any process and on any medium, for the sole purposes of private use and the proper conservation of the work, provided that these copies are not communicated to anyone.” But while the gallery’s role is to ensure the dissemination and transmission of works, one crucial point remains unresolved: how can we preserve, beyond the sound file itself, the concrete means of replaying and keeping a sound creation alive?

Consider, for example, the documentation policy developed by Apo33. The organisation has introduced a systematic methodology for recording and archiving all its activities: “Since 1999, we have put in place a method of systematically recording all our events, works, artistic processes and equipment, and making them accessible on our servers in a 100% autonomous way,” recalls Ottavi. Today, the protocol is highly structured: for each event, a dedicated workstation is assigned to documentation. The recording and dissemination equipment is optimised to ensure both the memory and the valorisation of the productions. “We have a machine dedicated exclusively to audio recording and streaming, at minimum in stereo and/or multitrack using the Ardour software, for later post-production in the studio and possibly a release on Fibrr Records, or online publication for archiving if the recordings are not officially valorised. And another dedicated machine for multi-platform video streaming and archiving (Twitch, YouTube, Facebook and PeerTube).” This conservation policy is also found in other structures, such as the sound creation studio Les Ensembles 2.2. “For each project, in addition to standard software backups, we export track by track, with and without processing. We also add the raw sounds, along with a description of the processing and how it is used. This allows us to reassemble the puzzle when we need to revisit the original creations, whatever the time elapsed. It’s designed for experts, capable of reproducing the creation with the tools available at any given moment,” explains Gaëtan Gromer, director of the Strasbourg-based organisation. This logic of conservation is integrated by different stakeholders in the projects, including developers.

“At Les Ensembles 2.2, we developed a software solution for geolocated sound creation: the GHO application. I made the developer aware of the importance of backward compatibility and of a community-based tool. In practice, all our projects run through the same application. This allows us to maintain the code, and there is a feature that lets you export your project as a zip file with all the information needed for conservation,” adds Gromer. These examples highlight the wide diversity of practices and resources mobilised to preserve digital works, even as most organisations and artists—lacking means—are unable to implement such policies.

In light of this, a first conclusion is offered by Lemouton: “In France, there are many conservation initiatives. But what we see is that these are projects that are not very durable or that depend on people who are personally invested in the topic. It shows that this is an issue that must be addressed within the broader framework of cultural policies.” In other words, the goal is not simply to delegate the question of sound conservation to individual organisations, but to equip them with the means to access lasting conditions of preservation. Until now, the topic has mobilised many institutions through inventory and digitisation campaigns that have made it possible to safeguard a portion of the emblematic repertoire. Numerous repositories bear witness to these efforts today: the electroacoustic database of SEAMUS (The Society for Electro-Acoustic Music in the United States), the ZKM’s mediaartbase, and the INA-GRM’s collections, among others. Other archives, such as the EMS (Experimental Music Studio at the University of Illinois), are still being processed.

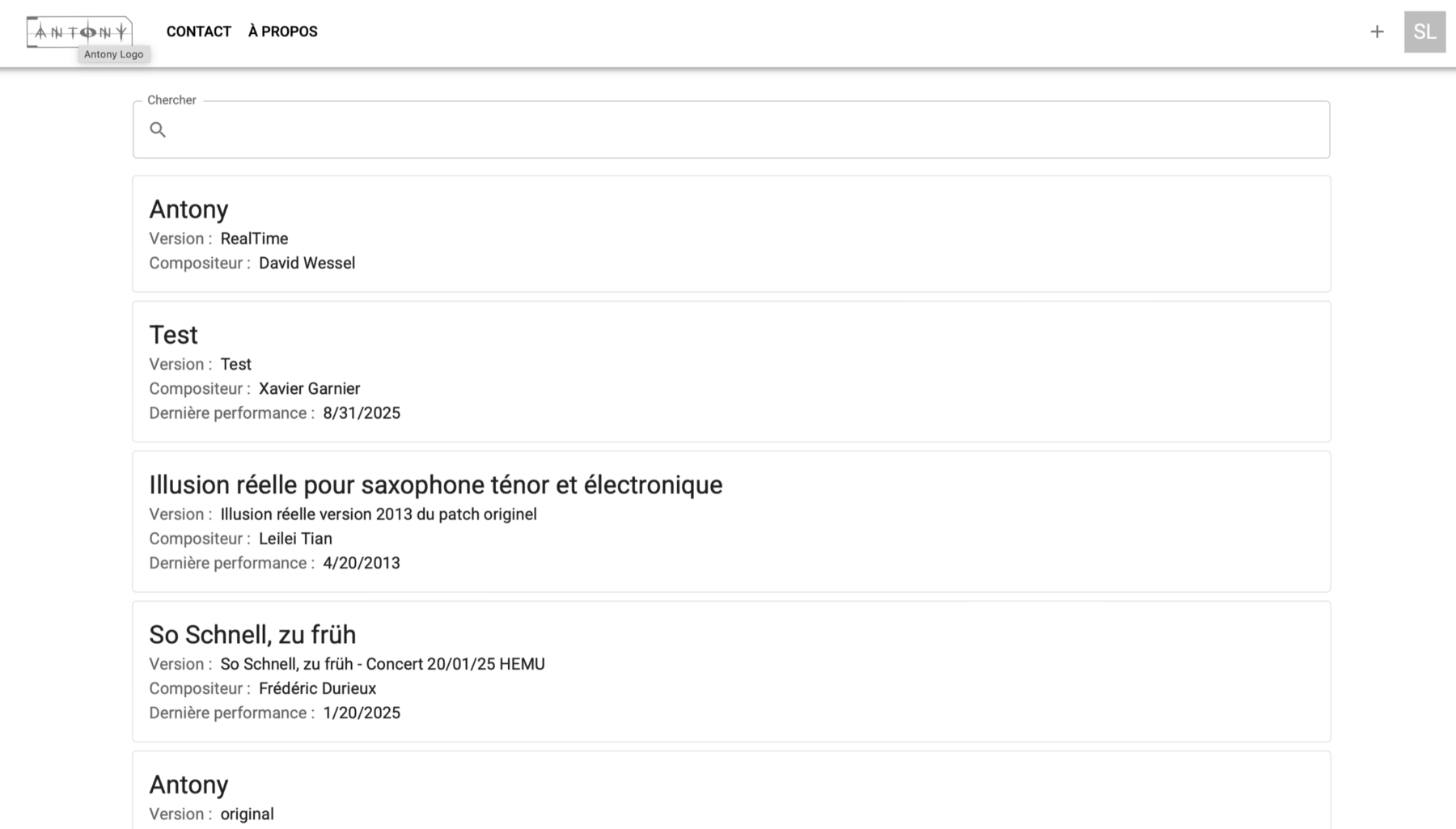

Up to this point, no lasting institutional initiative had made it possible to systematically organise the documentation and preservation of software, patches and environments specific to digital music. Building on these scattered attempts, however, a working group has launched a large-scale project scheduled to be implemented by the end of 2025. Its ambition? To establish a collaborative preservation of music involving electronics, through a remote digital repository of software environments and the creation of a documentary database. It is a first decisive step towards conserving the artistic processes behind digital sound works. Called the Antony project, this consortium is led by the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris, with support from the Ministry of Culture. Among the dozen partner organisations are IRCAM, the Maison de la Musique Contemporaine, several National Centres for Musical Creation (Grame, GMEM, GMEA, CIRM, Césaré, La Muse en Circuit…), as well as the BnF (Bibliothèque nationale de France) and the UMR STMS (Sciences et Technologies de la Musique et du Son). “The open-source platform will go online in January 2026, hosted by the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris. We’re beginning to open it up for beta testing,” says Lemouton, who is actively involved in the working group.

In concrete terms, Antony is a collaborative platform designed for cultural organisations and artists. It will offer, on the one hand, a metadata editing interface that allows users to document digital musical works according to a dedicated data model, and on the other, a repository system built to host, version and share the digital contents that define these works. The objective is twofold: to improve the preservation, research and dissemination of the repertoire using digital technologies, while facilitating the sharing, traceability and reuse of contents among users.

But will this platform truly be suited to the diversity of digital sound creations? The Antony project has been built precisely on a prior study of existing practices: “We began by observing practices in museums that host sound installations. There are protocols we drew inspiration from. We wanted to see whether our model, which works well for us, could be suitable for other organisations. An installation involves a great many variables,” notes Lemouton. Antony is also grounded in a free-software approach, with the possibility for users to develop new services according to their needs. However, this approach cannot replace a broader reflection on the documentation of immersive works, where it is just as important to account for the artistic process as for the sensory and emotional experience generated in audiences. Such an undertaking would also suppose opening up dialogue with the human and social sciences (anthropology, sociology, cognitive sciences…) in order to integrate audience studies into the documentation of works.

At the heart of these issues, two key words emerge: cooperation and pooling. That all organisations and artists may rely on common tools, in order to prevent entire swathes of our sound and digital heritage from disappearing. All the more so as many actors—such as Espace Gantner or the HACNUM network, which has set up a working group on conservation led by artist-researcher Jean-François Jégo—have been engaged with this topic for several years (see the panel “Collecting and Conserving Digital Artworks”). The challenge now is to meet this task collectively.