Between Installation and Video Games: When Alternative Controllers Shift the Codes of Gaming

Article published on 20 October 2025

Reading time: 12 minutes

Article published on 20 October 2025

Reading time: 12 minutes

While video games are still often associated with the home console, another indie scene is asserting itself on the margins. In it, artists and game designers create installation-based works that subvert traditional controllers. Gathered under the term “alternative controllers”, these creations champion the hacking of everyday objects and the reclaiming of physical space—often with a generous dose of humour. What exactly does this notion cover? Which artists make up this community? Can these installations still be considered video games? A dive into a creative movement that is now making its way beyond gaming circles.

At Ars Electronica in September 2025, four participants stand gathered around a screen, shifting from right to left, contorting themselves, trading bursts of laughter. In front of them, a display shows a kind of giant, revisited Pong. In Playing Democracy 2.0, artist Ling Tan explores the mechanisms of democracy through a collective game based on bodily movement. Here, participants can choose to cooperate, negotiate, or break the rules. Each gesture becomes a political act. Together or individually, players change the course of the game—even at the risk of triggering its collapse. Co-produced and presented at the Barbican Centre in 2024, this installation perfectly illustrates the spirit of alternative controllers: playful installations that put body, space and experience back at the heart of the work, increasingly present in the programming of cultural venues.

Let us first return to the origin of the term “alternative controller”. In the early 2010s, artists such as the collective One Life Remains began to assert a creative practice located at the intersection of design, gaming, and installation. At the same time, a few researchers, like anthropologist Nicolas Nova, took a close interest in gamepads and peripherals. In 2014, the Game Developers Conference (GDC)—the annual gathering of video game creators in San Francisco—dedicated part of its exhibition to independent projects, under the “altctrl” banner, that divert and rework traditional gamepads, keyboards, and mice. The initiative immediately resonated within the independent game community. “I discovered a new diversity of games. For me, it showed that there was a physical space—a materiality—for video games,” says Henri Morawski, production manager at Random Bazar, an association specialising in alternative controllers. Since then, alternative controllers have been studied in more depth, notably through the reference work of artist-researcher Tatiana Vilela dos Santos, with a PhD thesis defended in 2024: “Le mouvement altctrl, repenser la matérialité du jeu à l’ère de sa dématérialisation” (“The altctrl movement: rethinking the materiality of play in the era of its dematerialisation”).

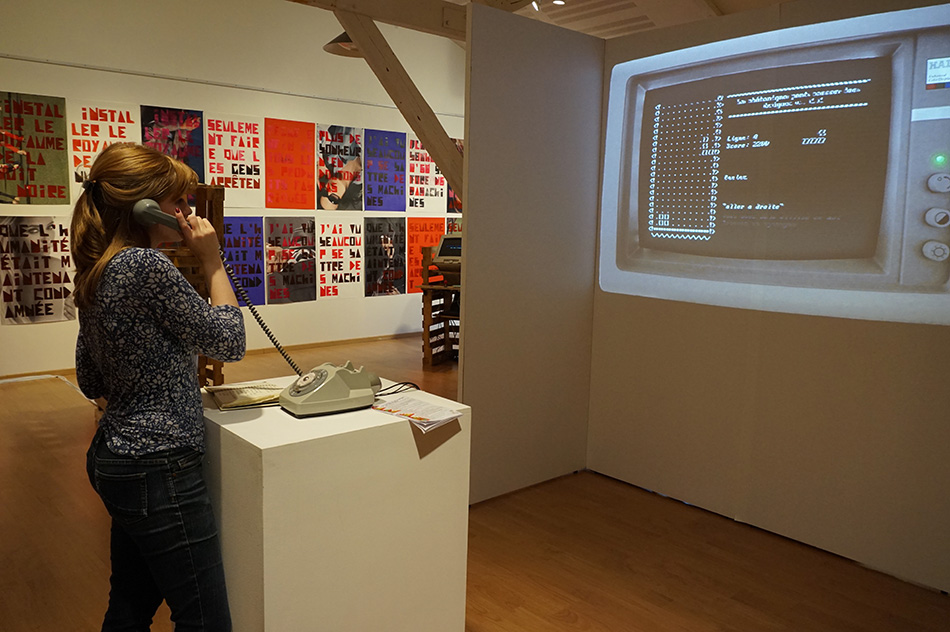

From the outset, we can observe two trends in alternative controllers: the first category aims to distort the screens, as seen in Line Wobbler, a work by artist and developer Robin Baumgarten. Here, this very minimalist game consists of a simple joystick and an LED strip. So, without a screen in the traditional sense. The second category, the more common one, includes works that repurpose controllers standardized by the gaming industry (gamepads, mice, keyboards, but also tablets, phones, etc.). An example is Scrollathon by Filipe Vilas-Boas, a race played by scrolling with the fingers. Or, following the same principle, Digitalympics by artist and teacher Florent Deloison, an athletics game inviting players to run a 110-metre hurdles race by scrolling with their fingers. Another is La rhétorique peut casser des briques, where each player must use voice ommands—speaking into a phone—to control the pieces. “The player has to talk to control a Tetris game. But there’s a constraint: each word can only be used once, so you have to find synonyms,” smiles Florent Deloison. Alternative controllers, extensively documented on the website Shake That Button, therefore raise questions about game mechanics, playability, and of course about pleasure and fun in art.

This philosophy of détourning and bypassing manifests in handmade interfaces, designed in a resolutely DIY spirit. “It’s really close to maker culture: craft-based fabrication, sharing, open source. Controllers are often designed in fab labs. With alternative controllers, I have a freedom I won’t find anywhere else,” explains artist Émilie Breslavetz, who collaborates with Léon Denise.

A MAZE. or Maker Faire have thus become benchmark events for this experimental scene. “Very often, we start prototyping with cardboard and tape,” continues Émilie Breslavetz. “We fund our works ourselves, so we often build them in low-tech ways. But a good controller can evolve: Crashboard, for example, had a second, more refined version following its public success.” Without always explicitly claiming the permacomputing movement (see the article Permacomputing: fleeting trend or lasting phenomenon?), these practices often share its principles: resource efficiency, technological sobriety, and reuse. Artist Antonin Fourneau recalls: “We had laughably small budgets. With Jankenpopp, we wondered how to produce ten installations with 500 euros. The solution: go to Emmaüs and buy 8-bit consoles for 5 euros. For 15 or 20 euros, we would simply modify the controller. Instead of a 1,000-euro computer, we could create an installation for just a few coins. It was video game ready-made.”

Yet this videogame ready-made is probably not an end in itself. “What interests me is the détournement: how you take an industrial object, coming from a cultural industry, and joyfully divert it from its original intention,” explains Florent Deloison. In other words, what matters is less the end result than the intention and approach. As an artist and teacher at ESAD Orléans, Deloison uses alternative controllers as a teaching tool. I ask my students to choose a game on an emulator and hijack its interface or its controller. It’s a fascinating exercise because it questions the very notion of interaction: we change the meaning of the game, reveal its limits, sometimes through deliberately absurd setups. Under those conditions, engagement is total.”

This collective and experimental approach can be seen in many public workshops, such as Make & Play, led by Tatiana Vilela dos Santos during the Stereogame event at Stereolux. Collectives like CTRL+ALT Baguette also contribute to this democratization by sharing videos and fabrication tutorials online. The same logic of reclaiming a work can be seen when showcasing these alternative controllers: “The interactivity of a video game allows you not to be subjected to the system. And the controller allows you to reverse that power dynamic,” comments Olivier Mauco, president of the European Video Game Observatory. An analysis that echoes the thesis How Alternative Game Controllers Foster Reflective Game Design by researcher Enric Granzotto Llagostera.

It is therefore hardly surprising to see alternative controllers making their way into museums today. First of all as mediation tools: “Gaming appears more and more in science museums, such as at the Cité des sciences. We learn better through experience—a pedagogy of making—than through the simple repetition of dogmatic discourses,” emphasises Olivier Mauco. But beyond mediation, more and more cultural institutions are taking an interest in these installation formats and their experiential potential. One of the most striking examples remains Eniarof, a key event bringing together around forty artists. Conceived in 2005 by Antonin Fourneau and inspired by the world of funfairs, Eniarof transforms attractions into hacked games, absurd interfaces, and playful interactive devices. “We celebrated our 35th edition in 2025. Eniarof is hosted by digital-art festivals or commissioned by cities,” says Antonin Fourneau. “At the beginning, alternative controllers were badly perceived, even within the video game scene: hacking retro gaming wasn’t always seen as a tribute. Today, new structures—immersive museums, hybrid venues such as Meow Wolf in the United States—are taking a closer interest.”

In France, Random Bazar is now looking to shine a spotlight on this vibrant scene through a dedicated festival. “We want to showcase this independent community and support it with two open calls. Our goal is to present brand-new installations,” explains Antoine Herren, co-founder of Random Bazar. The Dutch collective Katpatat’s piece Hoki Doki was selected as one of the winning projects. From 13 February to 7 March, around ten setups will be exhibited at the Shadok in Strasbourg, including Keyboard Olympics by the Mechbird collective and L’allumeur de réverbère, in which a player—stranded on an island—must build bridges using real pieces of wood. Ultimately, for Antoine Herren, the aim is to highlight “the diversity and creativity of alternative controllers.”

We are therefore dealing with a very real artistic movement—but one whose name remains somewhat fluid. The term alternative controller first and foremost serves to bring together a diverse range of game-based devices under a single banner, to make them easier to discuss and more visible. “We’d like this to become a genuine artistic movement. Its added value is its hybrid nature, which can find a place in different creative fields,” says Henri Morawski of Random Bazar. Some prefer other terms: hardware games, or playful installation, as Émilie Breslavetz does. “I distinguish alternative controllers without a screen, which are closer to digital art installations,” she explains. The artist, who has collaborated with the collective Néon Minuit on Miroir Arcade, a multiplayer installation controlled by a set of controllers (potentiometers, switches), adds: “Miroir Arcade is not a game: there is no game design; in fact, there is an erasure of game design. It is an interactive and playful installation.”

The concept of alternative controller, moreover, is not limited to the artistic sphere. The gaming industry itself has also experimented with forms of atypical controllers for several decades. “We’ve had some pretty surprising controllers: steering wheels, skis, devices where the game spills over into physical space, like dance games,” recalls Olivier Mauco. “Then came the era of the disappearing controller, with Kinect. Strictly speaking, the smartphone in Pokémon Go could be considered an alternative controller in the history of game interfaces.”

In the end, beyond labels—whether art history chooses to retain them or not—these alternative controllers seem to embody the profound influence of video games on contemporary creation. They extend its playful spirit, bear witness to an aesthetic of détournement that runs through part of today’s digital arts, and signal the gradual arrival of gaming in cultural institutions. And if they help draw audiences into cultural venues, that is, ultimately, what matters most.

Adrien Cornelissen