Artistic Creation: the real cost of Generative AI

Article published on 10 June 2025

Reading time: 7 min

Article published on 10 June 2025

Reading time: 7 min

In the cultural sector—often reluctant to talk about money—the rise of generative artificial intelligence raises major financial questions. What is the actual cost of these technologies for artists and cultural organisations? A seemingly simple question, yet one that reveals complex issues and a wide diversity of creative practices. Here is a closer look.

Artists, whether familiar with AI or not, may recognise themselves in this statement: finding the AI model that fits one’s artistic approach is a real puzzle. Amid this proliferation of tools (image, sound, text, and motion generation), one must understand what each model can actually do, experiment with it, assess its relevance to one’s intentions, and measure its adaptability to hybrid artistic practices. This initial exploration phase is made easier by the availability of freemium models, free trials, and open-source tools—though the latter are often deemed less user-friendly. Rather than comparing the prices of these tools, this article seeks to identify the costs associated with using generative AI. Because beyond subscription fees, other types of investment—especially in hardware—deserve attention. Cultural and creative industries, as well as the broader cultural sector, are particularly affected by the integration of artificial intelligence into their value chains.

Let’s start with the most obvious element: the cost of AI models. Proprietary LLMs such as GPT, Claude, Gemini or Mistral apply heterogeneous pricing grids that are difficult to understand for non-specialists. Usage is generally billed per token, the elementary unit of a language model (shorter than a word, but more stable for algorithmic processing). Most services offer relatively accessible monthly subscriptions (tens of euros per month) with no long-term commitment. But this flexibility hides a reality. “What we see is that artists are often hesitant in their early stages. They subscribe to several platforms, juggle trial periods and paid versions, sometimes for just a few dozen euros a month. In the end, your month of exploration can become very expensive,” observes Guillaume Lévesque, developer at Sporobole in Sherbrooke (Canada), who supports artists in AI residencies. Monthly costs can therefore add up quickly, especially for early adopters constantly seeking the latest innovations. And the return on investment—productivity gains often touted by tech giants—remains difficult to measure. An Afdas study expected at the end of 2025 will examine the actual effectiveness of AI in creative tasks.

In parallel, free alternatives also exist, notably open-source software, an ecosystem explored in more detail in Choosing Your AI Model: Proprietary, Free and Open-Source Software. This path is often favoured by “artists already engaged in ethical questions, particularly regarding data protection or the refusal to rely on cloud-based training,” notes Jean-Michaël Celerier, Director of Technological Development at the SAT in Montreal, which leads an ambitious research-creation programme on AI. Éric Desmarais, Director of Sporobole, offers further insight into the limited use of open-source tools: “We test all kinds of open-source solutions, but as soon as you want to integrate them into specific systems, the main obstacle is the cost of infrastructure, configuration time, installation and the hardware required.”

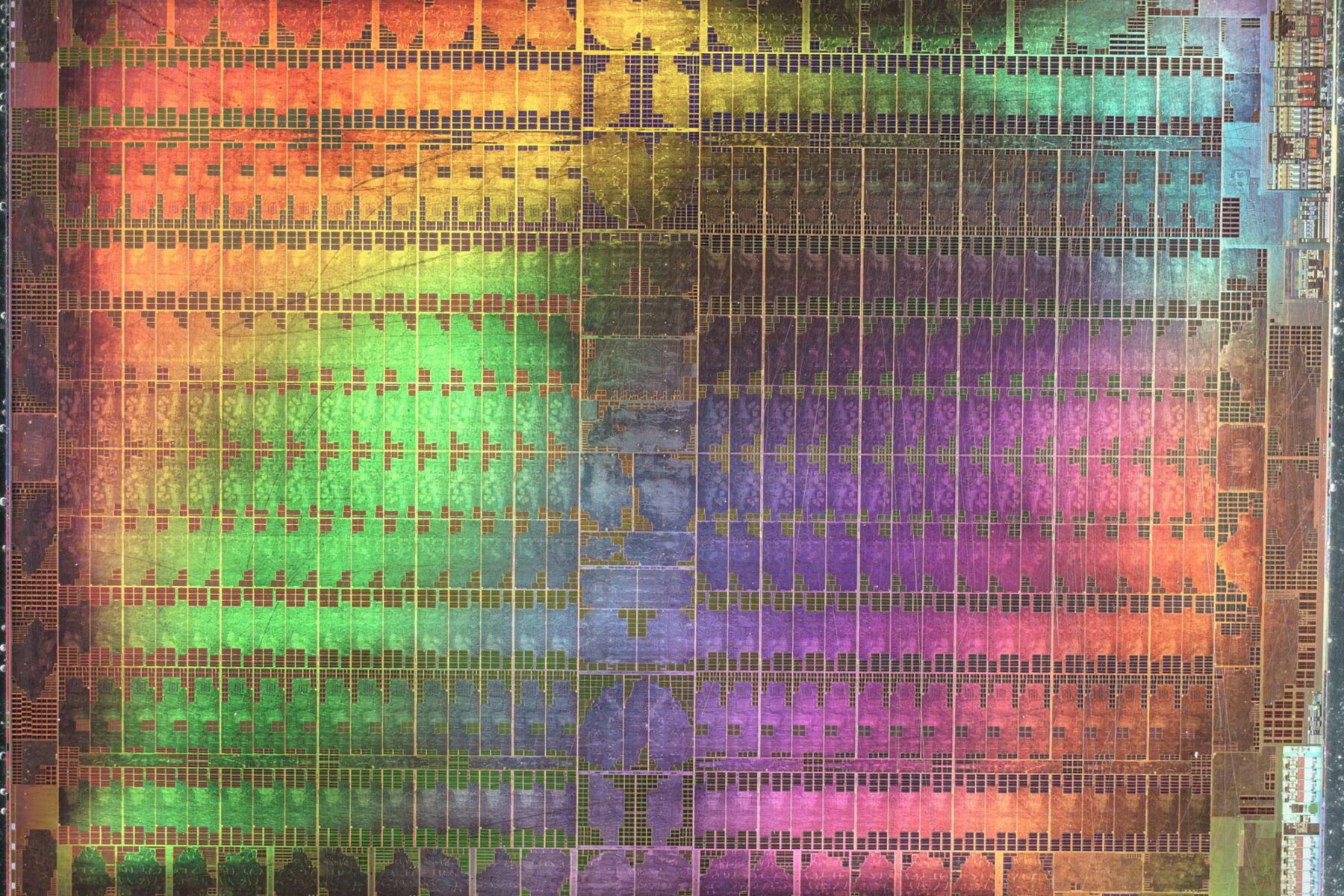

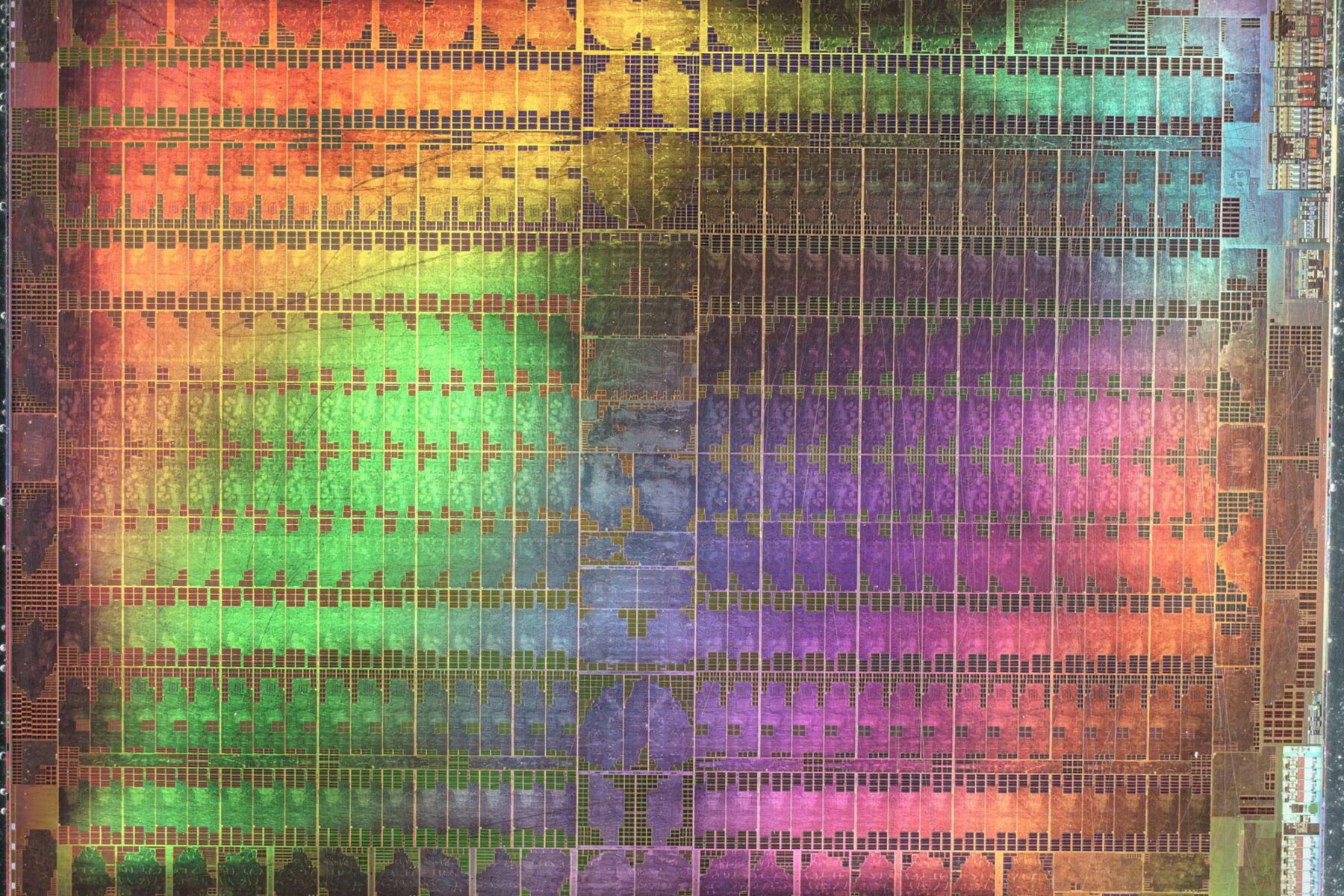

Hardware lies at the heart of the financial challenges surrounding AI. Training models requires significant computing power. Proprietary software usually relies on the cloud—remote servers provided either directly by the publishers (Meta, OpenAI…) or by specialised providers (AWS, Google Cloud, Azure, OVH…). Additional compute power can be purchased by the hour, costing a few cents per hour (or a few hundred euros per month). “In reality, hourly pricing is relatively modest for non-recurring projects,” says Guillaume Lévesque. Conversely, it becomes extremely costly for intensive, long-term use.

Another option is local hosting—installing servers physically in the studio or cultural institution. Although more complex to deploy, this solution is particularly relevant for projects requiring dedicated computing power, but also for security, fine network configuration, or stable connections. “There is real technical justification for having local infrastructure, especially when working with real-time interactivity. With the cloud, you quickly run into latency issues. A local machine is an entirely different experience. It’s an essential investment for performing arts and hybrid artistic practices,” explains Jean-Michaël Celerier.

This choice, however, involves major investment: purchase, installation, maintenance, and cooling of specialised machines, especially GPUs—highly coveted graphics processors. “We thought we had moved past these concerns, but AI brings us back to the fundamental issue of infrastructure. At Sporobole, we have a computer worth around 15,000 to 20,000 dollars, equipped with two RTX 4090 GPUs. Ideally, we would need three such machines to host more artists in residence. It’s a heavy investment for us, but strategically sound in the medium term,” says Éric Desmarais. A substantial cost indeed, but modest when compared to tech giants such as Meta, whose computing capacity is estimated at around 600,000 Nvidia H100 GPUs, each retailing at 30,000 euros.

In practice, cultural institutions have limited flexibility to invest in such expensive hardware. “We tried initiating a dialogue with NVIDIA, especially since PhD students and researchers used to be able to access GPUs for free,” says Jean-Michaël Celerier. This access strategy has been deployed for years at IRCAM in Paris, a dual-purpose institution as Hugues Vinet, Director of Innovation and Research Resources, recalls: “IRCAM is both an artistic creation centre and a research lab. This is why we have access to significant computing resources, including GPUs provided by NVIDIA, used to train internally developed models later applied in artistic projects.” IRCAM also leads PhD programmes in partnership with digital giants such as Meta, who contribute computing power. “These are win-win agreements: we bring very specific expertise, they provide computing power. It enables open research to emerge,” adds Hugues Vinet.

Beyond GPU acquisition, operating them continuously requires significant energy. Electricity consumption becomes a significant factor when deploying AI-based projects. For reference, a light configuration—with a single consumer or semi-professional GPU such as an RTX 3080 or 3090—represents about €30 per month in electricity. An intermediate setup, with two GPUs (such as RTX A5000), costs about €70 monthly. An advanced configuration—with four NVIDIA RTX 6000 GPUs—can require up to €200 per month. These amounts are negligible at an industrial scale but heavy for small cultural organisations or independent artists.

Another major obstacle is access to technical expertise. “Most AI engineers work in industry,” says Éric Desmarais. Working alongside artists in exploratory settings does not appeal to all developers. Add to this the issue of remuneration: AI skills are far more valued in commercial sectors. Guillaume Lévesque, creative developer at Sporobole, embodies this rare and sought-after hybrid profile: “My role is to find solutions to the problems artists encounter, set up infrastructures tailored to AI, and bridge technical requirements with creative issues. I’ve chosen my side—between industry and culture. But it’s true: there is a scarcity of people willing to work under more modest budget conditions.”

Despite these financial constraints, artists and cultural organisations are imagining collective strategies to embrace generative AI differently. The first lever involves questioning the dominant techno-maximalist approach, which equates creativity with uncompromising computing power. Jean-Michaël Celerier mentions a recent residency organised with MUTEK: “We hosted around ten artists working with AI. The question arose: should we rent high-performance machines? The alternative was to reduce computational power, even if it meant less spectacular results. But is that really a problem? For prototyping, optimal quality isn’t always necessary.” Artists willing to reduce their technical ambitions can rely on “lightweight” models (small language models or tiny models), less powerful by industrial standards but suitable for artistic objectives and capable of running on modest hardware. This approach complements that of IRCAM, which works on smaller corpora, less energy-intensive and with controlled rights. As Hugues Vinet explains: “Our challenge is also not to depend on large corporations or their models.”

This doesn’t prevent IRCAM from forming strategic partnerships with public institutions. “IRCAM’s lab is associated with the CNRS and Sorbonne University, which gives us access to the Jean Zay supercomputer,” says Vinet. Such access to high-performance infrastructure opens possibilities: it could inspire other cultural structures to strengthen ties with universities and art-science projects. These collaborations allow not only resource sharing, but also dialogue between fundamental research and contemporary creation (see the article PEPR-ICCARE: Creating the Conditions for a Genuine Encounter Between Scientific and Cultural Communities). In Canada, similar initiatives are emerging. “In the coming months, we’ll be developing a clustering tool, a distributed computing network based on our partners’ computers,” notes Éric Desmarais.

The challenge is clear: without a minimum of computing power and investment, institutions struggle to host highly motivated artists or support ambitious projects. The recent France 2030 call for projects, aimed at fostering the adoption of artificial intelligence and digital technologies by the cultural and creative industries, seems to move precisely in this direction. “A unique opportunity to accelerate the development and pooling of AI solutions designed by and for the various sectors of the CCI,” according to Rachida Dati, Minister of Culture (source). In this context, it is crucial not to overlook the cultural sector, already strained by numerous budget cuts (see the cartocrise tool). While AI comes with a cost, the value of culture is undeniable.